In the past the chestnut was called "bread tree:" its fruits were so nutritious that they were able to feed farmers during famines, or the inhabitants of areas where grains were scarce. Virtue of necessity: in a short time chestnut eaters found an effective strategy to stock up on carbohydrates by deceiving the eye and the palate. Pietro Andrea Mattioli, a great Sienese humanist and botanist who lived in the 16th century, narrates: "In the mountains where little wheat is harvested, chestnuts are dried and ground into flour which is skilfully used for making bread." So, what today is considered a trendy product - used to make pancake dough softer or to enrich vegetable soups with added flavour - a few centuries ago was the only source of sustenance available to destitute families. This explains why chestnut flour has inspired numerous recipes of the popular tradition, preserved in the cooking manuals that have made the history of Italian gastronomy (does the name Artusi ring a bell?).

Chestnut flour: characteristics and curiosities

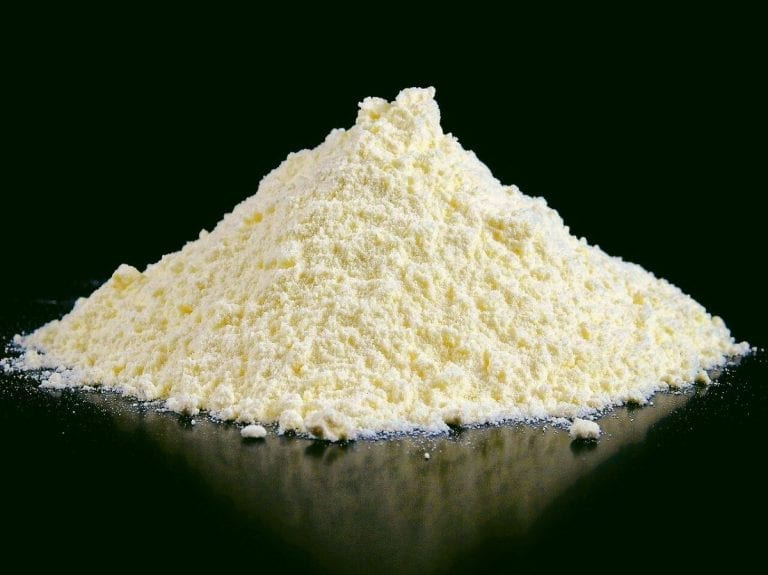

Like chickpea and almond flour, chestnut flour is also prepared by finely grinding the product after subjecting it to an accurate drying process, lasting 30-40 days, until the moisture contained in the fruit is completely eliminated. Compared to the first two, however, chestnut flour has a different colour - ranging from light hazelnut to ivory, depending on the degree of refinement - and a more decisive, typically sweet flavour. The flours made in the mountain areas with artisanal techniques, moreover, are characterised by a slight scent of smoke, due to the custom of roasting chestnuts before stone-grinding. In the kitchen, this ingredient, rich in starch, gives doughs a compact and dry texture, which is why it's always necessary to add a sufficient quantity of water to dilute the mixture before baking..

Tips for buying chestnut flour

The best way to purchase quality chestnut flour is to know the place where it is made. Fortunately, the ancient production methods have not been lost: in the Ligurian and Tuscan-Emilian Apennines there are still a few producres who use the traditional dryer, the metàto (a large stone hut where chestnut trunks are stacked as firewood) and practice manual peeling, beating the chestnuts with a wooden pestle with flat ends. In factories, on the other hand, the transformation is entirely entrusted to machinery, which allows to obtain very fine, homogeneous and residue-free flours. In both cases it's possible to purchase valid products, identifying the companies that select the raw material with care and commitment. To understand if we have made the right choice, then, we always pay attention to the appearance and flavour of the flour: for example, too dark a colour and an unbalanced taste towards bitter indicates that the husk of the fruit has not been correctly removed. On the contrary, the best flours are very sweet and sport a beige hue.

Chestnut flour: properties and nutritional values

Do you know that nutritionists suggest using this ingredient as a substitute for bread or potatoes? In fact, its nutritional values are characterised by high levels of carbohydrates (75-80%, against 60% of wheat flours) and by a low quantity of fats (3-4%); also fewer proteins, around 6% (a negligible value compared to 20-25% of legume flours). The notable intake of starches, however, must not discourage its consumption: chestnut flour is a real concentrate of fibers, capable of slowing down the body's absorption of sugars and inducing a prolonged sense of satiety. Other advantages? The absence of gluten, which makes it an ideal food to supplement the diet of people suffering from coeliac disease, and high levels of potassium, a mineral widely present in chestnuts. Furthermore, it is a valid tonic for those suffering from loss of appetite and is one of the least contaminated flours among those on the market, because chestnuts need very little treatment.

From chestnut flour to castagnaccio. Recipe and pairings

Born in Tuscany and "adopted" by numerous other Italian regions such as Lazio, Umbria and Emilia-Romagna, castagnaccio is one of the most popular dishes made with chestnut flour. Despite being a typically autumn dish, in fact, this thin and dense cake is prepared by small village residents throughout the year, including summer. The original recipe features chestnut flour along with water, olive oil, rosemary needles, pine nuts and raisins (with the occasional addition of orange peel and fennel seeds). The "cake" contains no sugar: it is the flour itself that gives the dough sweetness, simple and genuine. The perfect pairing? Try it with Vin Santo or an Aleatico dell'Elba Passito, two soft and fruity fortified wines. And, to cut through the smoky aftertaste of the flour, garnish your square of castagnaccio with a dollop of ricotta or mascarpone sweetened with honey and cacao powder.

Other traditional recipes that employ chestnut flour

Also in Tuscany (for a refresher course, we have a list of typical regional products) we find necci, fragrant crepes made from an amalgam of chestnut flour, water and confectioners sugar––usually baked in cast iron pans and traditionally stuffed with whipped ricotta––and manafregoli: a peasant dish from the area of Garfagnana, made by simmering cow's milk with chestnut flour over low heat until a thick and nourishing cream forms. Among other worthy of mention regional dishes are taiette from Lunigiana which are tagliatelle kneaded from a mix of chestnut flour and "0" flour; gnocchi with chestnut flour from Valchiavenna, dressed with mushrooms and mountain cheese; sweet chestnut ravioli from Piceno, kneaded and fried at the moment during the Marche region's Carnevale parades; sweet flour flan with chocolate, candied citron and almonds from Barga (a town in the province of Lucca), carefully described in Artusi's Science in the Kitchen.

Chestnut flour: other ulinary uses

How can we use chestnut flour to prepare something different from classic regional dishes? If you're planning a quick lunch we recommend making crepes: just mix the same amount of chestnut flour and water with a whisk and cook the mixture over low heat in a pan greased with olive oil, flipping it over when the surface starts to ripple. To test your skills, instead, you can attempt making bread, like typical Marocca di Casola. There are many recipes for this, from a gluten-free version with a mix of chestnut flour and rice flour, to one that involves the addition of semolina durum wheat. Choose one according to your tastes and, if you want to go crazy, use sourdough starter. For Sunday lunch there's nothing better than fresh egg pasta, softened by the sweet taste of toasted chestnuts (have you ever cooked chestnut tortelli?). Or a creamy soup made with flour thickened in the broth, rosemary, smoked pancetta and croutons. Any ideas for dessert? You will have a hard time choosing: from a chestnut and persimmon cream (here is Simone Rugiati's recipe) to cake with chestnut flour and dark chocolate, up to the Aosta Valley chestnut biscuits, there is something for everyone. However, we suggest you try bardinsecco, a very special Tuscan biscuit: below is the recipe of master Paolo Sacchetti of the Nuovo Mondo pastry shop in Prato.

Bardinsecco recipe by Paolo Sacchetti

Ingredients

100 g extra virgin olive oil

100 g confectioners sugar

100 g chestnut flour

100 g egg whites

100 g raisins

100 g pine nuts

Pour the dry ingredients in a stand mixer with the leaf attachment or in a bowl and start mixing them (in the second case, use spatula). Add the olive oil and egg whites previously beaten to stiff peaks in another container. When the mixture is homogeneously mixed, add the pine nuts and raisins. Spread the mixture as finely as possible on parchment paper or a silicone mat, then bake in the oven at 175-180°C for 8-10 minutes (until the biscuit turns hazelnut-coloured). Cut while still hot into equal sized squares. Once cool, store in a plastic bag or glass jar.

by Lucia Facchini

57 million bikers on vacation on farms, the Cycling Federation and Agriturist focus on cycle tourism

57 million bikers on vacation on farms, the Cycling Federation and Agriturist focus on cycle tourism A new era for Casa del Supplì: opens a new location and considers franchising

A new era for Casa del Supplì: opens a new location and considers franchising In Milan, a specialty café with gelato is opening near Bocconi University

In Milan, a specialty café with gelato is opening near Bocconi University Grillo phenomenon: Sicily is now betting on white wines

Grillo phenomenon: Sicily is now betting on white wines In Rome, a gelateria opens with only jarred ice creams. Master gelato maker Stefano Ferrara bans cones and cups

In Rome, a gelateria opens with only jarred ice creams. Master gelato maker Stefano Ferrara bans cones and cups