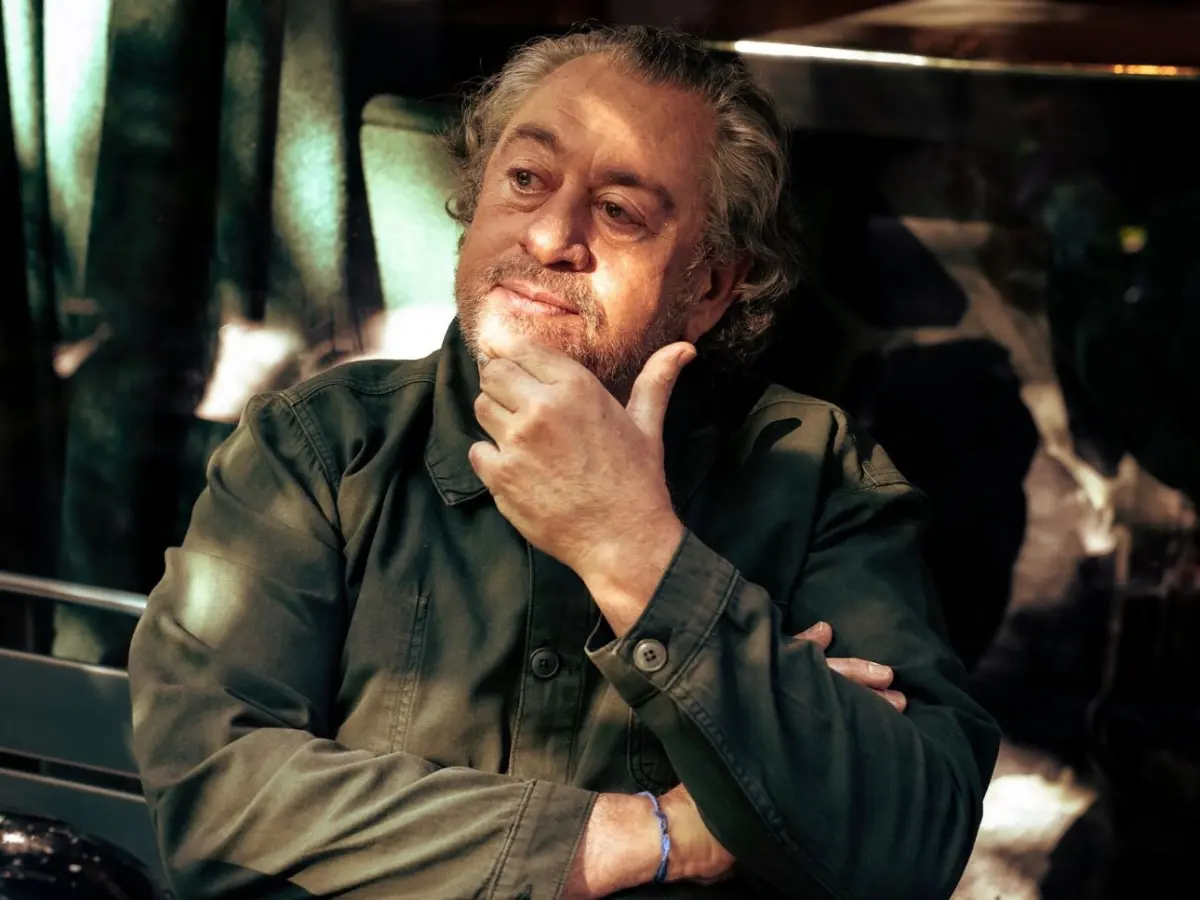

Salvo Foti, born in Catania in 1962, is an oenologist, author of several volumes on wine, consultant for renowned Sicilian companies in the Ragusa and Trapani areas, and a winemaker who has invested above all in Etnean viticulture, taking part in the birth of wine ventures that are now leaders in this unique territory. Some argue, with good reason, that he was the first to “invent” Etna wine as we understand it today.

You were a pioneer of Etna wine. One could say you “invented” it. How did it all begin?

Between the late 1980s and early 1990s in Sicily there was little interest in indigenous grape varieties and, in general, in traditional viticulture. The few bottled Sicilian wines considered of value bore labels such as “Chardonnay of…”, “Cabernet Sauvignon of…”, etc.

And the wines of Etna?

There were very few of us who believed in them. Etnean viticulture was considered of little interest and marginal. Even those who worked in it, like me, were given little consideration. Etna wines were snubbed also because the tastes of that time were very different from the characteristics of wines produced on the volcano. The Sicilian oenology that counted was something else entirely, and on the opposite side of the island, and everyone then agreed on this: oenologists, producers, journalists, critics, guides, and consumers. No important producer or renowned oenologist at that time would ever have dreamt of planting vineyards and making wines on an active volcano! The Etna wine of those years was sold in bulk, locally, almost exclusively to local consumers. Many grape growers sold their grapes. There were very few wineries on the volcano with both vineyards and cellars that bottled consistently (among them Cantine Villagrande and Murgo).

Many believe that the “renaissance” of Etna wines began in the early 2000s.

In reality, the renaissance of Etnean wines began in the early 1990s through my work and that of Giuseppe Benanti, and later other local producers: until 2000 there were no “outsiders” on Etna. It all stemmed from Giuseppe Benanti’s desire, in 1988, to become a producer, and from my research work – first historical, then technical-scientific – in collaboration with Professor Rocco Di Stefano, director of the Experimental Institute of Oenology in Asti, a great scientist and luminary of oenological chemistry.

Besides Benanti, who else took the first steps on Etna?

Alice Bonaccorsi, Valcerasa, followed soon after by Ciro Biondi, I Vigneri and Il Cantante (the winery of Mick Hucknall, leader of Simply Red).

Today’s producers owe you a lot…

Benanti and I, beyond production itself, from the early 1990s onwards were promoters of important communication and dissemination of Etnean viticulture, which aroused the curiosity and interest of technicians, journalists and commercial operators. All the producers, technicians and professionals of the sector who came afterwards found in the Benanti winery and its wines a point of reference.

Another turning point came when Etna was rediscovered by a group of “outsiders”.

Only ten years after the beginning of the “Renaissance of Etna wine”, therefore in the early 2000s, came three producers – Andrea Franchetti, Frank Cornelissen and Marc De Grazia – who gave a huge push not only in production, but above all in promotion and marketing, which made the Etnean territory one of the most renowned and respected in the world’s oenological heritage.

How has the Sicilian wine world changed since you started?

Rather than change, I would speak of awareness that we Sicilian producers have gained over the last thirty years. For a long time, Sicily was a “reservoir” of wine from which many northern Italian regions and some foreign countries sourced to boost their own production. It was cheap wine, sold in bulk, anonymous, with high alcohol content. Very alcoholic and not very pleasant: that was the cliché, until just a few years ago, about Sicilian wine.

What is the state of Etna wine today?

In the last twenty years, the number of Etnean bottling wineries has grown from about ten to more than 250. On Etna many producers have established themselves, local and non-local, Italian and foreign, with different production styles. Some with oenological experience, others without, some very technical, others improvised. The oenological renaissance and international attention have quickly made Etna a global oenological case. This can become a problem when those who invest on Etna do not produce “Etnean wines”, but simply wines “made” on Etna. Today, on Etna, coexist those inclined towards so-called natural wines, luxury wines, artisanal wines, fashionable wines, technological wines, industrial wines.

Does this worry you?

The concern is that the exponential and sudden growth that Etnean viticulture is experiencing leaves room for improvisation, uncontrolled and without planning: it is in this context that speculators find opportunities. The future scenario, under these conditions, is really difficult to imagine. The continuity over time of this important renaissance of the Etnean wine sector can only be achieved by promoting a programme of revaluation of the territory. Environmental sustainability cannot be ignored if we want to ensure long-term continuity for any human activity, and above all if we want to “hand back” to future generations a territory intact in its environmental and human values.

Is the future of Etnean sparkling wines, particularly from Carricante, promising?

For the production of Etnean sparkling wines, I consider Carricante grown in the higher zones of the volcano to be very suitable, where the grapes of this indigenous variety, and also of other varieties, can naturally achieve full ripeness while maintaining a proper acid-sugar balance, excellent for a sparkling base, without having to drastically bring forward the grape harvest, even into the summer.

Is there room for other indigenous grapes in the future?

On Etna there are other grape varieties that can be considered “indigenous” since they have been cultivated for a very long time and are little recognised, both legislatively and technically: for example Grenache, cultivated at high altitude, from one thousand metres upwards, on the north-western slopes of the volcano. Also Grecanico, Minnella Bianca and Minnella Nera, and other so-called “relic” varieties, today the subject of university research. For these grape varieties too, it is important to have the territory as the final objective. The grape variety alone, as the main objective, can become a fashion destined to fade away and have no future. We must prioritise territorial objectives: grape varieties and know-how can be transferred anywhere. The territory and the vineyard, no.

How would you define your way of making wine? Do you feel an affinity with natural wine?

“Naturalness” of a wine, for me, is the commitment to intervene as little as possible with external energies and products in the transformation of grapes into wine. Producing a wine is a human act, not a natural one. For this reason, we have always preferred to define our wines as “Human Wines” rather than “natural wines” or any other label. “Human Wine” for us means the continuation of the agricultural and viticultural practices of our ancestors, the use of the ancient agricultural system of the alberello and the palmento, the sharing and harmony of work with our collaborators and with our family. The goal of “Human Wines” is: to produce with respect for people and the environment.

How have tastes changed? And how do you think the wine world will evolve?

On the commercial side of wine I do not have the skills or knowledge to give an adequate answer. But I believe, at least for our Western civilisation, that wine will increasingly become a cultural component. A hedonistic fact, a symbolic and human ritual.

And what about dealcoholised wines – what role will they have?

“Dealcoholised wines”? I can only say that they have little to do with our wine culture.

The Top Italian Wines Roadshow returns to Kenya

The Top Italian Wines Roadshow returns to Kenya Why 'restraint is a virtue' for a top Prosecco producer

Why 'restraint is a virtue' for a top Prosecco producer Gambero Rosso in Nigeria: a new strategic market for Italian wine

Gambero Rosso in Nigeria: a new strategic market for Italian wine Meet the Italian viticulturist who manages an English vineyard

Meet the Italian viticulturist who manages an English vineyard The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day