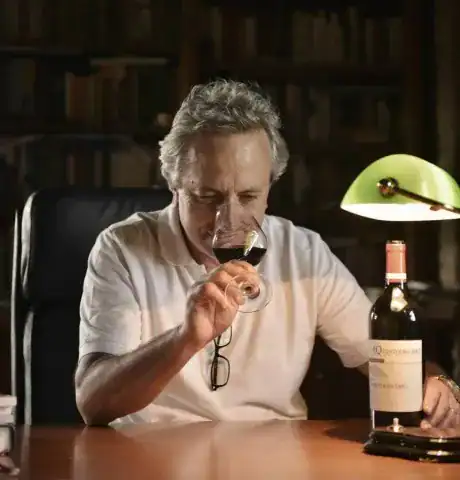

“There are no styles: wine should simply be an expression of the vineyard.” The vice-president of the International Organisation of Vine and Wine, Luigi Moio, speaking at VinoVip al Forte (where he received the Pino Khail Prize from the magazine Civiltà del bere), points the finger at standardisation. A winemaker himself in Irpinia (Cantina Quintodecimo) and professor of Oenology at the University of Naples Federico II, Moio told Askanews that wine should first and foremost be an agricultural project and that, therefore, quality and style must originate in the vineyard — starting with respect for the land and the harmony between plant, soil and climate, in other words: vocation.

Over the past 30 years, wines have become too standardised

These are concepts he had already expressed in Gambero Rosso, even going so far as to speak of the failure of organic viticulture: “Organic, conceived at a desk, can become a trap when the climate is against us.” On that occasion, he also explained why focusing too much on production techniques leads to homogenisation.

In his comments to Askanews, he also reflected on the mistakes made in communication, convinced that the current emphasis on production techniques has essentially overshadowed the importance of terroir.

“In the last thirty years, many have entered the world of wine, and this has increased demand. But uncontrolled growth creates confusion, and confusion creates panic and disorientation: too many ways of making wine have emerged, and even the Pasteurian foundations have been questioned, to the point of considering a sensory defect as a sign of typicity.”

On the contrary, Moio explains, the true sensory defect is standardisation. “Wine has always been fascinating thanks to its diversity, which must come from the place of production, the vineyard, the vintage: all of this is at risk of being lost, also due to so-called styles. Of course,” he clarifies, “we now understand processes better and can guide them, but the confusion created in recent years has led to a levelling down.”

Climate Change: Piwi and long-cycle varieties

There is another variable not to be underestimated: climate change, which, according to Moio, “favours the standardisation process. With rising temperatures and water shortages, development is accelerated and grapes ripen faster, with less acidity,” explains the professor. “Over-ripening is another homogenising process: it erases diversity, which must be avoided at all costs through science, experimentation, and technical knowledge.”

In the past, clonal selections favoured varieties that accumulated more sugar. Today, the opposite is needed: “we must select varieties that accumulate sugar more slowly and have longer ripening cycles. Italy is lucky in this regard, because our traditional varieties, in every region, are long-cycle. Even Primitivo, the earliest ripening, is still slower than many international grape varieties. Long-cycle varieties have an advantage because they better resist the acid degradation caused by excessive heat and long periods of sunshine.”

And speaking of varieties, Moio is not opposed to resistant vines: “They are a valid strategy, but the timescales for experimentation remain long.”

Relocation is not the solution: the great wine regions will remain

Then there is the issue of vineyard relocation to the north. “The problem,” reveals Moio, “is not moving vineyards, but continuing to produce great wines in the most prestigious regions, such as Bordeaux, Piedmont, Tuscany, Burgundy: we cannot imagine a future without these places. Relocation is not the only solution.”

It is true that in recent years, wine is being produced at new latitudes, from England to Sweden, with excellent results in some cases, as Moio reminds us: “Wine will be produced almost everywhere, demonstrating its universality — I’m not afraid of this spread. Chardonnay, Merlot and Cabernet became great because they spread across the world. But,” he emphasises again, “we cannot imagine the near future of wine without the historic areas that gave viticulture its charm and prestige.”

Uprooting to rebalance the market

On a very current topic — the upcoming harvest and concerns about overproduction — the professor admits that there is “really too much wine in the cellar at the moment. We need to rebalance supply and demand, possibly even through uprooting. Vines have been planted where they shouldn’t have been, ignoring vocation: the fundamental principle of the interaction between plant and environment.”

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day 'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca

'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market

Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers

Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers 'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'

'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'