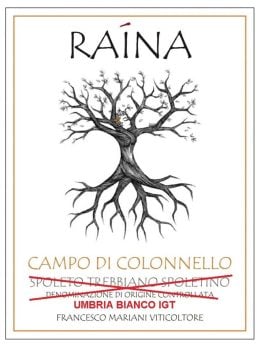

"The commissions that judge wines to award DOC and DOCG labels often go haywire when tasting bottles different from conventional ones." These are the words of Francesco Mariani, a winemaker at the Raìna winery, who has been practicing a less interventionist (so-called "natural") agriculture near Montefalco for years. His story is a small one that tells a larger tale. In the year 2022, in Umbria, to the general astonishment of industry professionals, Mariani immediately withdraws from the Montefalco and Spoleto DOCs. All his wines are then downgraded to Umbria IGT. The decision came after yet another rejection of the 2021 Trebbiano Spoletino, "reviewable by five out of five commissioners for color alteration, evident oxidation, and lack of specific characteristics." Tired of continuous rejections, he decided to continue selling his wines without the coveted labels. "The time for controversy is over," he wrote on Facebook, "and the Don Quixote-like battles against windmills. This system doesn't change, so it's time to step aside."

The Raìna case and the downgraded wines

The system that "doesn't change," in Mariani's words, is that of tasting commissions composed of oenologists and tasters. This is a topic also addressed by Report in the new wine investigation that aired on February 18, albeit hastily. As Professor Michele Antonio Fino wrote on Gambero Rosso, this is the only criticism that the program directed by Sigfrido Ranucci hits the mark on. Today, tasting commissions are often structured to favor a way of making wine, which is rarely the less standardized and non-interventionist one. To correct this distortion, years ago, FIVI, the Italian Federation of Independent Winemakers (the largest in the "natural" constellation), proposed that each tasting commission should always include a winemaker-producer with at least ten years of experience. A proposal that fell on deaf ears.

Today, for a winery to reintroduce the Designation of Origin, it must submit its wines to both analytical and organoleptic evaluations. And these evaluations are precisely carried out by a commission, one for each designation. "A system that does not always reflect reality," says Mariani. Certainly, not all natural wines are rejected; many pass and obtain the designation without problems. However, his case remains glaring: the Trebbiano Campo di Colonnello is a well-made wine appreciated by both the public and critics.

The wine is "reviewable"

"For several years, I had problems with wine certifications," says Mariani. "They identified macerations as oxidation, scents not perfectly in line with the regulations, nonexistent microbiological problems." And the wine was classified as "reviewed" or "not suitable." According to Mariani, "the commissions are composed of tasters, enologists, and technicians from large conventional wineries often far from our way of working." The regulations that set the rules for obtaining designations "sometimes, not always, do not reflect new tastes." A hurdle that led the winery to completely leave the Designation. "Even if we lose some customers who need the label," wrote the winemaker from Montefalco two years ago, "this doesn't scare us. First, because we no longer intend to compromise in any way. Second, because the sense of liberation is greater than the possible commercial repercussions. It's regrettable because I have always put the territory and quality above all else. It's a painful but now unavoidable choice."

The oil always moves north, reaching England. How the map of olive trees is changing due to climate change

The oil always moves north, reaching England. How the map of olive trees is changing due to climate change The Nobel Sandwich we tried at CERN, just steps from antimatter

The Nobel Sandwich we tried at CERN, just steps from antimatter The two young talents from Gattinara revolutionising Italian cuisine

The two young talents from Gattinara revolutionising Italian cuisine Here is the Meditation Wine of the Year according to Gambero Rosso

Here is the Meditation Wine of the Year according to Gambero Rosso The 6 new 'Tre Forchette' restaurants of Gambero Rosso: here they are

The 6 new 'Tre Forchette' restaurants of Gambero Rosso: here they are