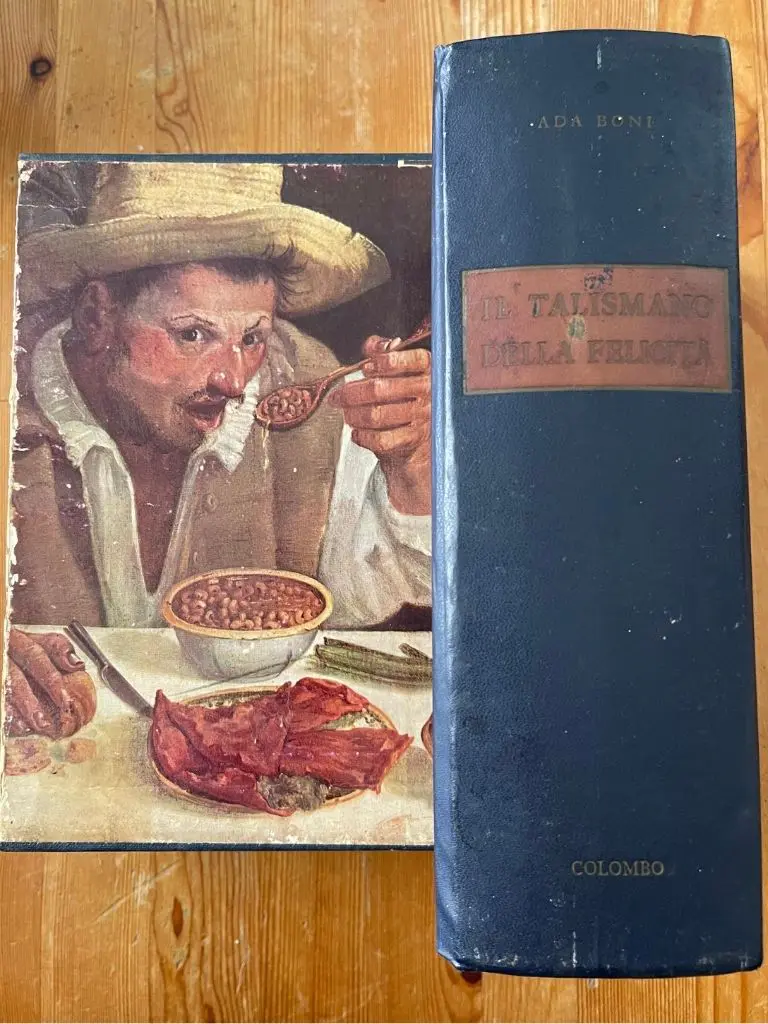

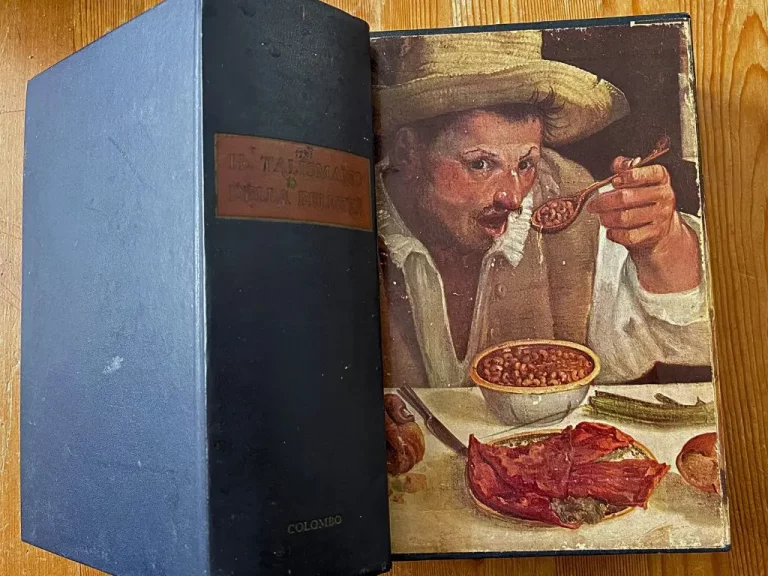

For a hundred years, a timeworn volume has graced every Italian kitchen: Il Talismano della Felicità by Ada Boni. With The Bean Eater by Annibale Carracci on its cover, this timeless book has shaped generations of home cooks, offering recipes, advice, and a model of everyday cooking that also serves as an affirmation of identity.

Now, that text—written for the Italian public a century ago—crosses the Atlantic in a complete English translation. It is a publishing achievement born from years of research and persistence: The New York Times called it “an almost maniacal mission.” But what does it mean, for Italian cuisine, to see its most domestic book become accessible to cooks in America?

The representation of Italy through its cuisine

On 28 October 2025, the first complete English translation of Il Talismano della Felicità will be published in the United States, with 1,680 recipes faithfully rendered in the language of the Bard, complete with converted measurements and commentary aimed at preserving the original spirit. Until now, the only English edition dated back to 1950: an adaptation for the American market, trimmed, with altered ingredients and editorial liberties to make it more “usable” overseas. It spoke English, but it was not the true voice of Ada Boni.

The idea of starting from scratch and translating the work in its entirety was almost accidental: editor Michael Szczerban, while working on Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat by Samin Nosrat, heard of Il Talismano, present in every Italian home, and decided to acquire the publishing rights. After countless searches, phone calls, and dead ends, contact with a great-grandnephew of Ada Boni turned his obsession into a concrete project. Across the ocean, the author is virtually unknown—except to the millions of Italians who emigrated.

Getty Images

Portrait of Ada Boni, an author who expressed individuality

Ada Giaquinto was born in Rome in 1881, making the Eternal City the centre of her editorial and cultural activity: she was a journalist, publisher, and writer active from the 1910s to the post-war period. She showed a special interest in cooking from childhood, beginning to cook at the age of ten, encouraged by her paternal uncle Adolfo Giaquinto, a well-known chef and founder of the culinary magazine Il Messaggero della cucina in 1903—one of the first periodicals entirely dedicated to Italian cuisine.

Ada married young, to Enrico Boni, heir to a family of Roman goldsmiths: a sculptor, painter, photographer, critic, music lover, writer, passionate gourmet, and close friend of haute cuisine pioneer Auguste Escoffier. More than just a soulmate, Enrico was Ada’s intellectual partner and collaborator. Together they founded Preziosa in 1915, a subscription magazine collecting recipes, domestic advice, and research materials that would later flow into Il Talismano.

The early editions (from 1925 to 1933) reflect personal experiences and travels across Italy’s regions. Boni’s method combined editorial rigour, field research, and public contribution, compiling recipes sent in by Preziosa readers and adapting them into an encyclopaedic format. This approach transformed the book into a true domestic manual—intended for newlywed women of the bourgeoisie and middle class seeking practical, authoritative guidance in the kitchen.

Identity in cooking as an intellectual value

The book is meticulous and profound, especially regarding cooking techniques—from achieving perfect frying to the trick for a soft sponge cake, to the preparation of jams following strict hygienic standards. But how did a woman born at the end of the 19th century, in an era when women cooked only at home, become so influential in the lives of thousands of women—helping, often unknowingly, to pave the way for today’s female entrepreneurs and chefs?

Across its thousand-plus pages, Il Talismano della Felicità offers not only recipes and etiquette tips: in it, Boni speaks directly to the women of her time, suggesting that cooking is a joy, but also part of one’s daily identity—an art with intellectual value. Her work sought to preserve culinary and domestic practices undergoing rapid transformation amid the country’s urbanisation and modernisation.

Following the author’s explicit wishes, the volume was adapted with each new edition to reflect the needs, tastes, and rhythms of different social classes. Over time, Il Talismano grew to more than two thousand recipes, becoming a household object, continually reprinted and given as a wedding gift. Its widespread presence in Italy and among emigrant communities meant that generations learned to cook “the home way” through its pages. This made Ada Boni a central figure in Italian domestic culinary culture. Over the century, Il Talismano has never gone out of print, selling over one million copies.

1968 edition, photo by Eleonora Baldwin

Reception in the United States

It is precisely this enduring bond with the Italian public that makes the new translation of this recipe-book-cum-essay such a symbolic turning point. Among Italian-American chefs, the announcement of the full edition has already generated excitement: many recall their families’ worn-out copies of Il Talismano as their first encounter with Italian cooking in emigrant homes.

One of its most famous readers and students, Marcella Hazan, learned from Ada Boni’s book. When she arrived in the United States as a young bride in the 1950s, Il Talismano della Felicità became her first guide in the kitchen. That experience would lead her to become the most authoritative interpreter of Italian cuisine in America.

The idea that there will now be a full, “uncut” English version of Il Talismano is cause for emotion—a cultural milestone signalling the recognition of Italian cooking not merely as an exportable product but as a universal language. In an era when Italian gastronomy is often reduced to clichés, returning Boni’s original work to the international public is a way to reaffirm the importance of our domestic culinary tradition.

There is, however, a lingering concern that the English edition might lose some of its essence: the imperial measurements, ingredient substitutions, and the author’s dry tone will all have to withstand translation without sacrificing authenticity.

The complete translation of Il Talismano della Felicità opens the domestic Italian experience of the past hundred years to the world—a narrative that makes everyday cooking a living language. If it can cross oceans without losing its original voice, it will have performed its own small miracle.

'Campo de’ Fiori is no longer a market': The transformation that no one talks about

'Campo de’ Fiori is no longer a market': The transformation that no one talks about 'Excellent products will remain excellent' – but does Old World wine have to adapt to survive?

'Excellent products will remain excellent' – but does Old World wine have to adapt to survive? Why 'the rules are still being written' for non-alcoholic drinks

Why 'the rules are still being written' for non-alcoholic drinks 'Why are we doing the same things again and again if they are not working?'

'Why are we doing the same things again and again if they are not working?' 'You cannot imagine how magnetic Etna is!'

'You cannot imagine how magnetic Etna is!'