Celebrating Saturn, the god of time, wealth, abundance and agriculture (to name but a few of his responsibilities), Saturnalia's roots likely go back to an Ancient Greek festival. In true Roman style, certain traditions were 'borrowed' from their neighbours from across the Adriatic. Coinciding with the winter solstice, this religious festival eventually developed into a week-long holiday filled with parties.

The second century satirist Lucian of Samosata's work Saturnalia features a dialogue between Saturn (or 'Kronos', to use his Greek name) and his priest. In the text, Saturn makes it clear that this is no time for toiling:

"During my week the serious is barred; no business allowed. Drinking and being drunk, noise and games and dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of tremulous hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water – such are the functions over which I preside."

One indication that many (though, of course, not all) would stop working during this week is that Roman men would swap their togas, the ancient equivalent of a business suit, for a more relaxed tunic

Although modern scholarship disputes the idea that Saturnalia was the direct ancestor of Christmas, there are clear similarities between how we celebrate during December 2025 and how those in the Roman Empire did so 2,000 years ago.

Gifting

The giving of presents was a key component of the Saturnalia celebrations.

“Rich people were expecting good presents from their clients. It was decided that those with less funds could give you a candle, but you could give your client something better, so that you didn’t put a burden on your clients," says Sally Grainger, a food historian and writer specialising in Ancient Roman cookery, and the world's leading authority on garum, the ubiquitous fermented fish sauce.

"You have very basic things like figs and dates and mushrooms and truffles and luxury fish sauce, which was my favourite, but also things like silverware, writing materials, toothpicks and perfume – everything that we give today, they gave then," says Grainger.

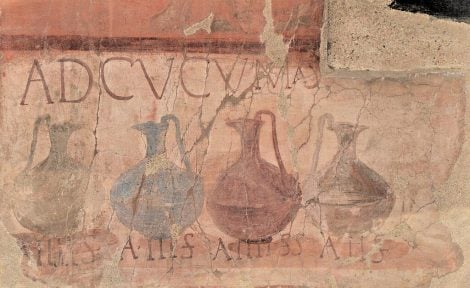

A fresco of Saturn discovered in Pompeii

Foodstuffs were certainly a popular gift, as evidenced by the Epigrams of the poet Marcus Valerius Martialis, better known as Martial. These short verses reveal the huge range of what might be exchanged during the festival.

Some of these food gifts could be fairly simple.

"This sausage that has reached you at midwinter time had reached me before Saturn’s seven days." – Martial, LXXII A Sausage

Others could be much more elaborate. One Epigram refers to an edible sculpture of Priapus, the well-endowed Greek god of fertility.

"If you want a full stomach, you can eat our Priapus; though you gnaw his very genitals, you will be clean." – Martial, LXIX Priapus made of flour

Feasting

"Feasting is something that happens in Roman society all year round because there are festivals every couple of weeks for one deity or another," says Grainger. "Any excuse for a festival, any excuse for a feast."

For the less fortunate in society, they could partake of a modest feast with some roasted meat at the Temple of Saturn. But, for those Romans wanting to flaunt their wealth, a nice joint of meat would simply not do.

"An ordinary household might have a sacrificial lamb, or a pig if you were a bit wealthier, and you would have a feast with your family and all those who work for you, including your slaves," Grainger explains.

Pork is a meat that is the focus of one of Martial's Epigrams on Saturnalia.

"This pig will make you a good Saturnalia; he fed on acorns among the foaming boars." – Martial, LXX A Pig

"Roasted meat is associated with the sacrifice and religious festivals, and so ordinary people did eat a certain amount of meat because it was part of that experience," continues Grainger. "This meant that the wealthy people did not want to eat just roast meat at their feasts – they have things like game, seafood, lots and lots of oysters, and offal – the more obscure the organ, the more elite. Because one lamb only has two kidneys and a liver, if you have a dish made entirely from liver, it means that you’ve had access to more than one carcass, so you’re displaying your wealth."

Sally Grainger

While the prevalence of quinto quarto cuts such as tripe and intestines in modern Roman cookery is a celebration of frugal cucina povera, it was their wealthy ancient antecedents who had a taste for parts of the animal which are all too often relegated to the butcher's bin in the 21st century.

"Things like ‘prairie oysters’ [a euphemism for testicles] were very popular, and to have them from many different kinds of animals – not just cows and sheep, but animals like hares too – showed that you were elite. To us, it seems bizarre, but for them it was highly desirable because these parts were so rare," says Grainger.

One luxury piece of offal which as retained its popularity among elites over the millennia is the sweetbread. The great first century cookbook writer Apicius, author of De Re Coquinaria (On Cookery) used these glands of calves or lambs in a number of his recipes, including the somewhat inappropriately-named 'Potted Salad' which contains chopped sweetbreads, as well as a ragout which combines them with oily fish, pork dumplings and chicken livers.

Another popular piece of offal was the brain. Apicius has a recipe for a leg of pork which is stuffed with calf's brains and myrtle sausage and then roasted. As strange as the exact ingredients may seem, the idea of stuffing animals with parts of other animals is one still seen in the modern Christmas Dinner.

Drinking

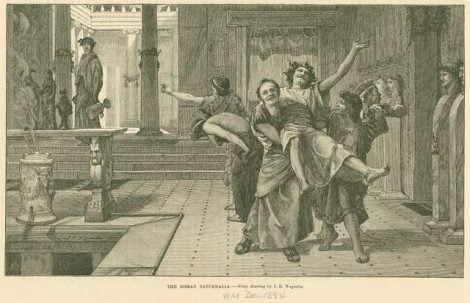

One key aspect of Saturnalia is the element of role reversal. Slaves would not only be permitted to dine with their masters, but on one particular day of the festivities the head of the household and his sons would actually serve the slaves.

"They [the slaves] were allowed to drink, gamble, be rowdy and generally have a good time – this is the one time of the year when this is allowed," says Grainger, though she notes that slaves would gamble for things such as nuts, rather than money.

Indeed, slaves could find themselves wielding a surprising degree of power during Saturnalia.

"In individual households, someone would be elected as master of the feast. It could be a popular slave, it doesn’t have to be a member of the free family. This master of the feast dictated the festivities, what games and fun they would have," Grainger reveals. "In ordinary feasting for the rest of the year you have what is called a magister bibendi, a master of drinking, who would decide on the ratio of water to wine. Neat wine was frowned upon, so the magister bibendi would determine the state of drunkenness of the guests – would the evening need livening up, or are the guests a bit too drunk. I suspect this role was also given to the master of the feast at Saturnalia."

A fresco advertising wine discovered in Herculaneum. Image credit: Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany

Unsurprisingly, the imbibing of alcohol was considered necessary to really celebrate Saturn, with cries of 'Io Saturnalia!' heard on the streets during the week's festivities. Among those to complain about excessive revelry at this time of year was the Stoic philosopher, statesman, and first century precursor to Ebenezer Scrooge, Seneca:

"License is given to the general merrymaking. Everything resounds with mighty preparations – as if the Saturnalia differed at all from the usual business day! So true it is that the difference is nil, that I regard as correct the remark of the man who said: ‘Once December was a month, now it is a year'."

Later in the same letter, Seneca moderates his opposition to the holiday:

"It shows much more courage to remain dry and sober when the mob is drunk and vomiting, but it shows greater self-control to refuse to withdraw oneself and to do what the crowd does, but in a different way – thus neither making oneself conspicuous nor becoming one of the crowd. For one may keep holiday without extravagance."

As for what Seneca's compatriots were drinking, spiced wine was a festive tipple, though it's not quite like the mulled wine that is commonplace in European Christmas markets today. Mulsum was a popular pre-meal aperitivo made by combining wine with honey, pepper and mastic – it could be served hot or cold, but not in between: "What was not desirable in an elite setting was to have it at room temperature – you had to have the means of heating or cooling it."

Grainger notes that towards the end of the Western Roman Empire, by which time Christianity was outpacing the traditional pantheon of gods, including Saturn, more 'Medieval' spices, such as cinnamon and ginger, began to appear in drinks recipes, with a kind of hippocras, effectively a proto-mulled wine, becoming popular.

Saturnalia outside of Rome

Even far from Rome, on the frozen fringes of the Empire, Saturnalia was still celebrated.

"Wherever the Romans went, they took their culture with them – a culture of drinking wine, of spices in food, of reclining to dine, and of celebrating these festivals," says Grainger.

One source of evidence for Saturnalia festivities comes from Hadrian's Wall, the defensive border that divided Britain and marked the northernmost reach of the Roman Empire.

Hadrian's Wall in winter: Image credit: Mike Quinn

Wooden tablets discovered at Vindolanda, one of the major forts along the wall, reveal that securing supplies for the end of the year was a priority for the garrisons. Some dated to around the time of Saturnalia list provisions at the fort, including a large volume of Celtic beer.

One tablet in particular, now in the British Museum, features a correspondence between two slaves at Vindolanda and reads:

"For the Saturnalia, I ask you, brother, to see to them at a price of four or six asses and radishes to the value of not less than half a denarius. Farewell, brother."

Not Christmas, but not far off

Of course, it was the rise of Christianity in the Roman Empire which would lead to Saturnalia falling out of favour, but, if one discards certain eccentricities, Saturnalia is a holiday which seems remarkably similar to the celebration of Christmas today: spending time with family, giving gifts, eating and drinking too much, and finding a cause for cheer during the longest nights of the year. There really is nothing new under the midwinter sun. Io Saturnalia!

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day 'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca

'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market

Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers

Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers 'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'

'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'