by Raffaele Mosca

Say Vermentino and you say summer. You find it there, on tables with fish and vegetable-based lunches, chilling in the ice bucket in a pure relaxation setting, with a tune playing in the background. Distinctive traits? It has the good fortune of adapting perfectly by the sea and of carrying the atmosphere of the Riviera through its aromas. In short, a very fashionable, trendy wine.

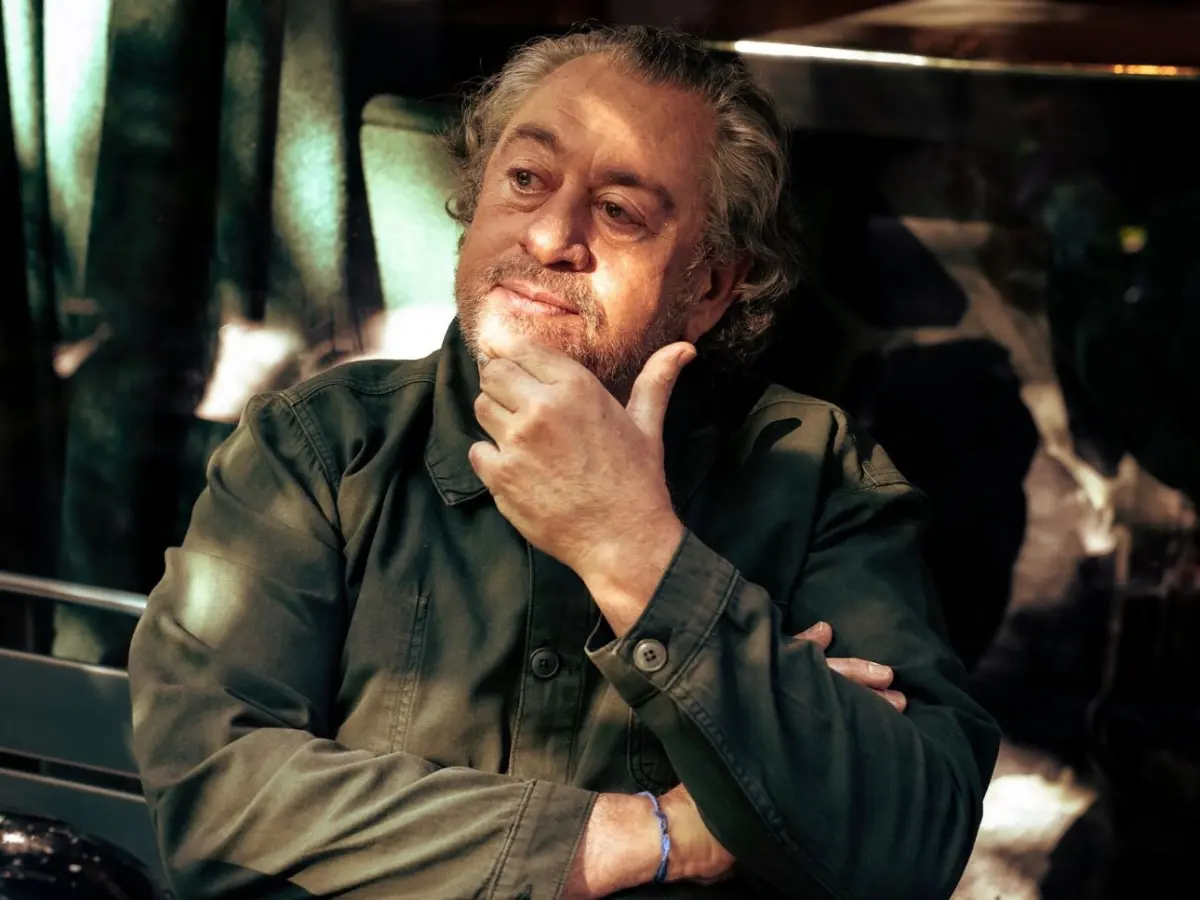

The interview with Diego Bosoni

And if, in some cases, the limit is a certain lack of depth and originality, in the Colli di Luni, on the border between Liguria and Tuscany, you find versions with great character. We had a chat with Diego Bosoni, the most important producer of the area. His real passion? Music.

The cover of this month’s issue on newsstands dedicated to Vermentino

The secret of Vermentino: freshness and ease

The first question to Diego Bosoni could only be this: What’s behind its boom in recent years?

“Well, it’s beyond question that an important qualitative value is the foundation – replies the owner of Lunae – first of all because it expresses something different depending on where it’s planted (and it works well in several regions, ed.). And also because contemporaneity is its strength: today’s wine lover doesn’t look for structure and power, but freshness and ease of drinking.”

So, has it established itself as the opposite of those heavy, oaky whites that were fine twenty years ago but have now become tiresome?

“Absolutely yes. But here with us it’s not fashion: it’s an integral part of the history of the Colli di Luni. And there was even a period here when the wood imprint and richness were sought after. But my father was never fond of that style and right from the start he moved towards something that combined complexity with smoothness. Today, seeing all this attention for this approach makes us very happy.”

So you don’t fear that the fact Vermentino is growing a little everywhere might create inflation and damage the reputation of the variety?

“This thought exists and we often discuss it with colleagues from the area. I believe, however, that if we in the Colli di Luni can maintain a certain qualitative level, we won’t have problems. Of course, there are fluctuations linked to market trends, and it’s likely that, as with other fashions, there will be a moment when it fades. But if you can truly give value to what you do, the risk doesn’t exist. The closest example is music: genres go out of fashion, but the artist, if he keeps his inspiration and reputation high, doesn’t run the risk of going under!”

The wine sector is going through a complicated moment. You, who produce a “trendy wine”, what do you think of this situation?

It would be foolish to say we are immune. But we consider ourselves lucky: probably precisely because of our ability to build a solid reputation, we maintain a certain stability. But it must also be said that, unlike others, we’ve had a very regular growth, without extreme peaks.

Most Italian companies have invested enormously in internationalisation. Instead, you sell 80% of your production in Italy.

“We start from here: we began from the surrounding area and gradually expanded into neighbouring territories, Tuscany and Liguria first, then throughout Italy. Abroad we arrived much later.”

What is the great advantage and the great disadvantage of working mainly in Italy?

“The advantage is maintaining a chain of human relations that you can hardly create elsewhere. The risk with export is becoming impersonal and detached from the final consumer, not knowing where your wine really ends up. The problem is extreme fragmentation: you sell small quantities to an enormous number of clients. But we’re used to it because our vineyard is like that too: over 50 hectares owned – plus more from our growers – all fragmented into small plots.”

How does it feel to be the largest producer in a denomination – and in a region – of small winegrowers?

“In reality, size has never been our concern: we work like all Ligurian winegrowers. Of course, we have to run a company with over 500,000 bottles a year. And in any case, we do it as farmers: we don’t have an entrepreneurial background. We’re the biggest in Liguria, but in other regions we’d be considered medium-small. And we try to be leaders and create synergy, building a circuit that can elevate the territory, also through Ca’ Lunae, our structure dedicated to wine tourism with an adjoining restaurant.”

In your opinion, is it more important to enhance the Colli di Luni territory or the Vermentino grape?

“You must enhance the place through the grape and the grape through the place. Of course, we’re something apart compared to other areas devoted to Vermentino, but we owe this success to the grape and depriving ourselves of its name – as they are doing in other areas – would be unthinkable. Also because it’s the best interpreter of this territory between sea and mountains, between Tuscany and Liguria, with a wealth of nuances within.”

Among all Vermentino, is Colli di Luni perhaps stylistically the most northern?

“In some ways yes: surely this is a coastal area, not a mountain climate. But the Apuan Alps are close and the mountain breezes always descend to refresh the vineyards: from there comes this aromatic elegance and the acidity that sometimes recalls more northern territories.”

The longevity of Vermentino: it tends to be drunk fresh, but tastings show that it evolves in a fascinating and unusual way.

“It’s a wine that doesn’t necessarily need to be aged: it’s enjoyable right from the start. But it has a dual key: drink it young and you appreciate its fruit and acidity. In evolution, if the grapes and zones are right, it sheds its more exuberant part and develops great complexity, while always maintaining its Mediterranean identity intertwined with that hydrocarbon touch that enthusiasts love.”

Yet, reaching the point of producing a version specifically designed for ageing wasn’t easy.

“Not at all: here, if you want, you can sell everything straight away. When in 2008 I first tried to make a limited edition wine with longer ageing, released almost four years after the harvest, I called it Numero Chiuso because I thought it was a ‘one shot’: my father thought it made no sense to wait so long. But then he changed his mind: he never told me directly, but, seeing the results, he allowed me to continue!”

To a colleague of yours who wants to aim for success with a white wine, what would you recommend, as a great white wine producer?

“To be introspective, not to force yourself to align with a specific style and not to be carried away by dreams or convictions that are inconsistent with the place where you are. And then a good mortgage for investments in vineyard and cellar… And moreover, regardless of the type of wine, a bit of meditation to always keep calm!”

The Top Italian Wines Roadshow returns to Kenya

The Top Italian Wines Roadshow returns to Kenya Why 'restraint is a virtue' for a top Prosecco producer

Why 'restraint is a virtue' for a top Prosecco producer Gambero Rosso in Nigeria: a new strategic market for Italian wine

Gambero Rosso in Nigeria: a new strategic market for Italian wine Meet the Italian viticulturist who manages an English vineyard

Meet the Italian viticulturist who manages an English vineyard The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day