by Ilaria Corona

It’s called “tonno”, but it’s rabbit. And it’s not a joke. The name merely refers to the method used to preserve the meat: slowly boiled, hand-shredded, then immersed in oil and left to rest for days. The result is a white, tender, and flavoursome meat that visually resembles tinned tuna in oil.

A practical answer to an everyday problem

In the Piedmontese countryside, for centuries rabbit was one of the most common sources of protein. Easy to raise, it needed little food, lived around the home, and didn’t require complex structures. Beef or pork wasn’t always available, and game was unpredictable. Rabbit, on the other hand, offered some consistency.

At the time, fridges didn’t exist, and preserving meat was essential. The only option was to rely on homemade methods: slow cooking, deboning, resting, and immersing the meat in olive oil, which acts as a barrier against air and moisture, allowing the product to keep for weeks. In this way, rabbit meat changes both in texture and flavour, to the point of resembling preserved tuna. Over time, the meat softens and absorbs the oil and aromas, becoming more flavourful.

Foto credit: Facebook @marco__brioschi

The ingenuity of the friars

There’s a curious, almost legendary tale linked to this dish. It’s said that, in the 19th century, friars from a convent in Avigliana, near Turin, devised a clever workaround to the prohibition against eating meat during Lent: they cooked rabbit, preserved it in oil, and passed it off as tuna. In doing so, they were able to eat meat without facing punishment.

The recipe

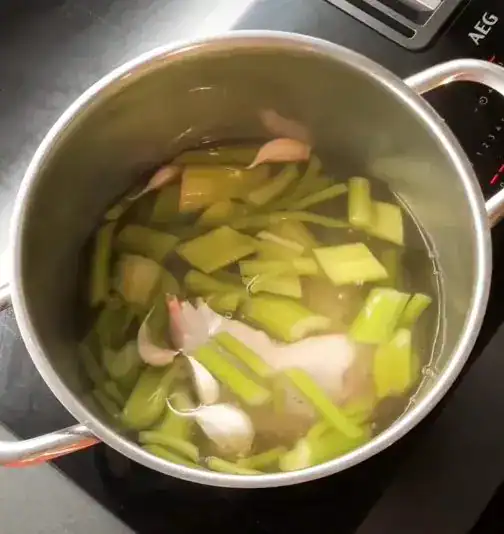

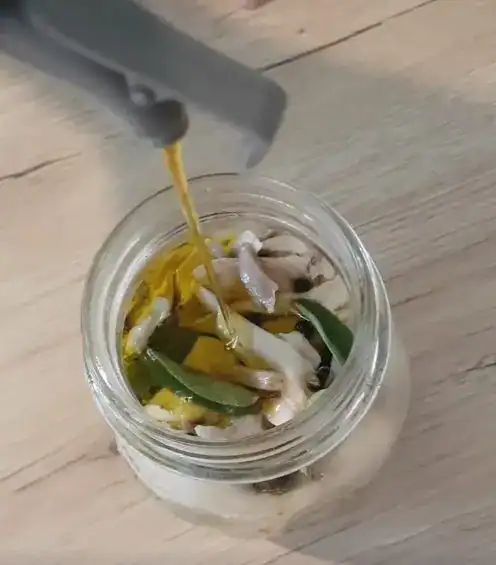

Tonno di coniglio isn’t a quick dish to prepare. The meat must be boiled in water with onion or garlic, celery, carrot, white wine and spices. After cooking, the rabbit is left to cool, deboned, and shredded by hand. It’s then placed in glass or terracotta jars with garlic, bay leaves, whole peppercorns, and covered in oil. The resting period is part of the recipe: at least two days in the fridge, but those who follow tradition will wait a week or more.

Foto credit: Facebook @marco__brioschi

In the past, families would prepare several jars for the winter. Tonno di coniglio would feature in stuffed breads, salads, and impromptu lunches. It often made an appearance during celebrations, alongside Russian salad, vitello tonnato, and other cold dishes typical of Piedmontese cuisine.

From home cooking to the trattoria

Over time, tonno di coniglio moved from home kitchens to trattoria menus. Today, it’s often served as a starter in Piedmontese restaurants, mostly in its classic version. But some do reimagine it: some add capers, others use less traditional spices, or serve the meat with boiled eggs or crunchy salad leaves.

Cover photo: Facebook “Non C’è Amore Più Sincero Di Quello Per Il Cibo”

'You cannot imagine how magnetic Etna is!'

'You cannot imagine how magnetic Etna is!' 'To be the global platform, we must take everyone and everything into account'

'To be the global platform, we must take everyone and everything into account' What did Italian producers think of Wine Paris 2026?

What did Italian producers think of Wine Paris 2026? The pizza that’s taking the Winter Olympics by storm

The pizza that’s taking the Winter Olympics by storm Where to eat in Central Rome (while avoiding the tourist traps)

Where to eat in Central Rome (while avoiding the tourist traps)