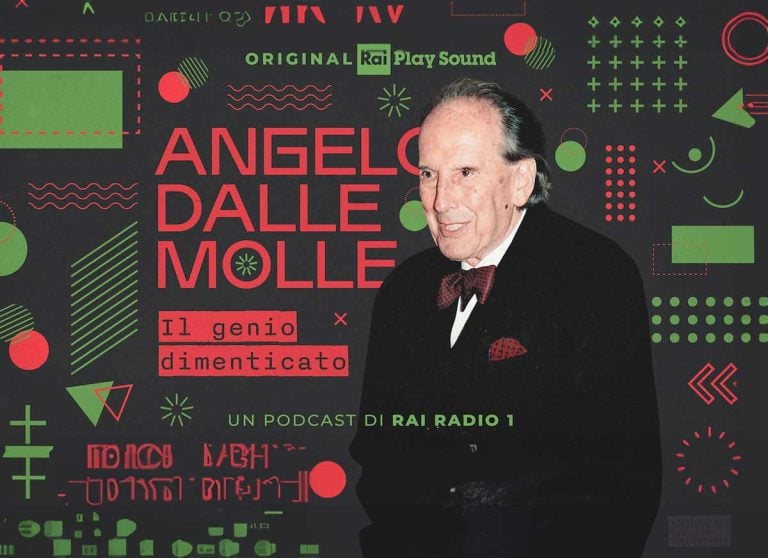

On Made in Italy Day, Radio1 Rai launches a podcast by Massimo Cerofolini dedicated to an Italian genius almost unknown to the general public: Angelo Dalle Molle, the creator of Cynar in the 1950s (together with Rino Dondi Pinton), who half a century ago was also building electric cars, designing car sharing and charging stations, and later dedicated himself to research in artificial intelligence and the digital world. The story of this man, born in Mestre in 1908 and who passed away in 2001, is truly incredible. Dalle Molle put his volcanic creativity and brilliant curiosity at the service of the future: inventing, communicating, and studying how to improve people’s lives. All while consistently and stubbornly going against the grain.

From AvioBar to Cynar

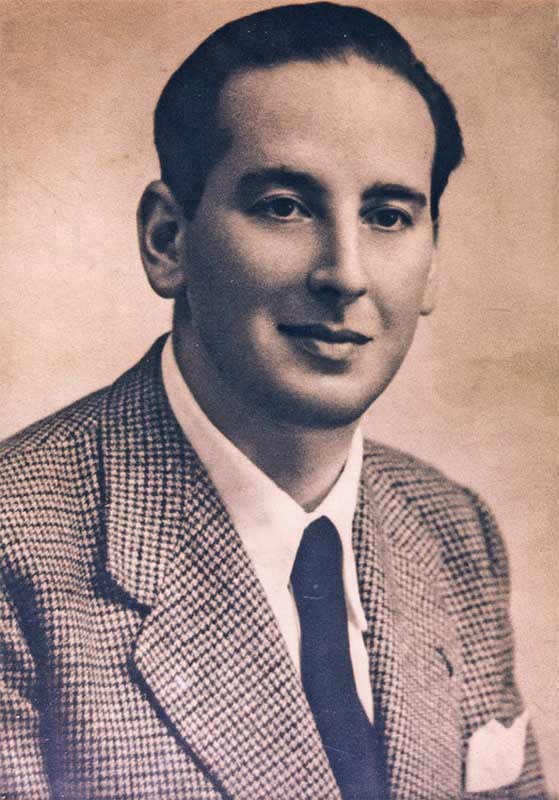

The 5-episode podcast by Massimo Cerofolini retraces the life of this character to whom both Musk (with Tesla) and Sam Altman (with ChatGPT) are arguably indebted. But let’s tell his story step by step—this figure to whom modernity owes so much and who embodied the ideal of an enlightened entrepreneur, unfortunately ignored by the mainstream. In 1935, still in his twenties, Angelo dropped out of university and persuaded his family to buy the struggling Pezziol company, which produced famous spirits like Vov. Twelve years later, he launched the AvioBar initiative as part of the Grandi Marche Associate project (also his idea): an American cargo plane was transformed into a flying bar that, in 1947, toured Italy in 10 stages. It was a promotional campaign not only for the Grandi Marche Associate Group but also for other players in the sector. The initiative was a huge success.

Angelo was deeply affected by the desolation—seen from above—of an Italy reduced to rubble by the recently ended war, and he developed a desire to help with reconstruction in a meaningful way. The following year, Dalle Molle achieved what many considered impossible: creating a liqueur from artichokes, a vegetable never before used in the industry, chosen for its health benefits. After two years of experimentation with chemist Rino Dondi Pinton, Dalle Molle overcame widespread scepticism and, in 1950, launched his creation, Cynar, with a spectacular campaign that won over the entire country thanks to an extensive network and innovative marketing strategies. The success of the bitter exceeded all expectations: two million bottles sold in just one year.

Dalle Molle leaves Cynar and turns to electric cars

In 1966, Angelo hired actor Ernesto Calindri and launched the iconic advert "against the stress of modern life," in which Calindri calmly sips Cynar amid traffic. The adverts quickly became vehicles for social messaging, including road safety and political protest campaigns. In 1958, he founded La via aperta, a magazine featuring contributions from key cultural and political figures of the 20th century, such as Don Sturzo and Schuman.

By the early 1970s, Cynar and the company’s other products were selling over 40 million bottles a year. But at the height of success, Dalle Molle lost interest in business and turned his attention to two new fields: computing and the environment. After selling his shares in 1973, he bought a spectacular Palladian-style villa near Padua and devoted himself full-time to his visionary projects. It was here that he set up a mechanical workshop and began building electric cars and designing a network of car sharing and charging stations.

Projects and realisations (far) ahead of their time

The project attracted strong interest in many Italian cities, with complete executive plans, and was eventually realised in Brussels, where for years it linked two university campuses. But despite initial enthusiasm, Italian bureaucracy and politics thwarted the initiative. Local governments dragged their feet, excuses multiplied, and by the mid-1980s Dalle Molle was forced to abandon the electric car hire project.

“Italy would have to wait twenty years to see tentative versions of what he had already built,” says podcast author Massimo Cerofolini from Raiplaysound.

A Foundation for Artificial Intelligence

In the 1970s, after leaving the Cynar company, alongside his electric car sharing project, Angelo Dalle Molle shifted his research focus to computing, decades ahead of his time. In addition to the Dalle Molle Foundation for Quality of Life, he established three pioneering institutes on artificial intelligence in Italian-speaking Switzerland: ISCO in Geneva (1976) for semantic and cognitive studies, IDSIA in Lugano (1988) for AI and neural networks, and a centre in Martigny (1991) focused on perceptual artificial intelligence.

These were the dark years of AI research, when governments around the world were pulling funding from the field. But Angelo didn’t give up—he carried on alone and undeterred. Dalle Molle funded fundamental research into language, neural networks, and machine learning. Time would prove him right: his Foundation is now recognised as a cornerstone in the history leading up to today’s AI revolutions, such as ChatGPT. As early as 1997, Business Week ranked it among the world’s five most influential AI research centres, alongside institutions such as MIT in Boston and the University of California, Berkeley.

The human side and legacy of a genius

Cerofolini’s podcast doesn’t overlook the human side of this genius. Dalle Molle had a turbulent personal life: within five years, he cheated on his wife with four different women—each unaware of the others—by whom he had five children. Then, at age 90, he married his long-time collaborator Eleonora.

In his work, Cerofolini explains, Dalle Molle showed many similarities to humanist entrepreneur Adriano Olivetti: he treated collaborators with deep respect, encouraged their creativity and dignity, rejected purely production-driven logic, and always put the human being before the machine. “He was an accessible yet demanding leader, able to inspire commitment to his often non-conformist projects. A patron and long-term thinker, he engaged with the culture of his time while remaining intrinsically reserved, preferring the shadows to the spotlight.” This is how the podcast’s author portrays him.

It was precisely this shyness and particular character—coupled, no doubt, with a degree of collective superficiality—that helped make him a “forgotten genius”, whose most precious legacy remains his call to always put human beings, not profit, at the centre of progress.

The Consorzio Vino Chianti heads to Nigeria: 'A historic step towards opening new routes for Italian wine'

The Consorzio Vino Chianti heads to Nigeria: 'A historic step towards opening new routes for Italian wine' 'The Mercosur agreement is also good for Prosecco'

'The Mercosur agreement is also good for Prosecco' The bottle where Vino Nobile di Montepulciano meets Milanese design

The bottle where Vino Nobile di Montepulciano meets Milanese design Pinot Noir overtakes other red grapes in Oltrepò Pavese

Pinot Noir overtakes other red grapes in Oltrepò Pavese What does 2026 hold for New York pizza?

What does 2026 hold for New York pizza?