Does the concept of terroir apply to spirits? A relevant question for those tied to the winemaking tradition, where the connection between agricultural land and agri-food production is taken for granted. Examples of this connection include Doc and Igp, designations protected and guaranteed by the EU. Paradoxically, in the world of spirits – despite being subject to numerous regulations – it's not quite the same. There is no geographical connection between the place where the product is distilled and the raw material used for distillation. For instance, a Speyside Whisky - which, by regulation, must be distilled and aged entirely within the boundaries of Scotland - is not restricted in terms of the raw material used and can be distilled from Ukrainian wheat. Different are the models of French Cognac and Mexican Tequila: in both cases, regulations tightly control the type of plant (grapes and agave, respectively) that can be used and the production area it must come from. However, even with rules tied to territories, there is generally no connection between the farmer and the distiller, as is the case with wine.

The "craft distillery"

In a world where few large multinational corporations have acquired most independent artisanal brands and facilities, the production strategy aims for quantity and consistency of product standards rather than the territoriality of raw materials. Distillation often becomes a tool to smooth out differences resulting from various supplies to make the final result reproducible in series. It doesn't matter if the starting wine would have been particularly suitable for enhancing its characteristics related to vineyard exposure or a favorable vintage, or if, conversely, a poor farmer in Jalisco had to pull the agaves out of the ground after only 4 years (the minimum age according to Tequila regulations) instead of waiting for the right degree of ripening and sugar concentration

However, there is a "but." While a significant part of the market standardizes and consolidates into increasingly powerful industrial entities on the financial and production fronts, the last decades have seen the explosion of the phenomenon – worldwide – of Craft Distilleries, which in Italy we would call artisanal. This new generation of passionate "artisan" entrepreneurs has, for the first time, begun to consider that to talk about territoriality, it is necessary to consider the entire supply chain starting from agriculture. In other words, not only eating but also drinking is an agricultural act!

The distillery that starts from Chianti

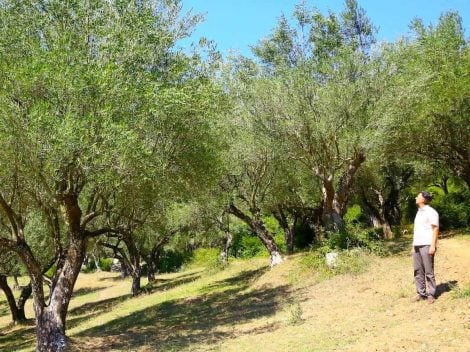

If things are changing globally, Italy is not exempt from this new wave revitalizing distilleries. Just go to Chianti Classico to understand it. Here, one of the very few Italian laboratories (4 or 5 in total, excluding "grapperies," which are a different world) that distill their "own alcohol" is based. While many micro-distilleries in recent years have fired up their stills, most of them purchase "neutral" alcohol (often of non-European origin) and then distill it with various botanicals to create their "own" gin. Different is the case of Winestillery, which has given life to an innovative fusion of winemaking and distillation. Founded by the Chioccioli Altadonna family, it is now led by Enrico, a master distiller who trained through extensive experiences abroad and returned to Chianti with revolutionary ideas. Enrico first went to France to understand Cognac (but also barrels, woods); then to America, following the traces of Whiskey; then he returned with a very clear project in mind: to distill – amidst the vineyards – the Chianti produced by his family, transforming it into a gin with Tuscan botanicals. To understand the importance of this wine in the production of spirits, just try the vodka derived from it: absolutely (and fortunately) not "neutral" and rich in flavors and scents linked to its origin.

Today, Winestillery offers a diverse range of spirits: from London Dry to Old Tom (made sweet by a careful balance of ingredients and aging, more than sugar) and Sloe Gin (called Slow Gin, made from grape pomace), in addition to the aforementioned wine vodka. Winestillery opens new horizons in the world of spirits, taking the concept of terroir far beyond that defined by wine.

The rebirth of single malt

Islay, the queen of the Hebrides, has always been considered the homeland of peaty whiskies. It is here that Kilchoman opened in 2005, the first new distillery on the Scottish island in over 120 years. Kilchoman is an agricultural micro-distillery that works from field to still and aims to produce a single malt tied to the land. Despite the annual production already exceeding the considerable volume of 450,000 liters (which is less than half of what one of the single "giants" on the same coasts would produce on average), Kilchoman aims for self-sufficiency. It increases the "100% Islay" labels each year, providing a different narrative of the symbol distillate of this land, highlighting the diversities linked to various vintages, different crops, and aging conditions pursued on the island. While maintaining an intimate size, Kilchoman manages to embrace modernity without losing the essence of tradition. The internal Malting Floor, one of the few active in Scotland, significantly contributes to this identity battle by keeping alive the practice of malting just steps away from the barley fields.

The location of the farm, near the Atlantic Ocean, also has a significant impact on the character of the whiskies, adding evident and intriguing marine notes to the typical peaty ones of Islay.

The miracle of French whisky

If the French set out to do something, especially if it is an excellent product, it is rare that they do not do it well. In recent decades, also driven by the growing domestic consumption, France has started to produce excellent whiskies, benefiting from its long experience in aging traditional Cognac and Armagnac, supported by the long history of cereal cultivation and malting for beer production. Among all the new active companies, one stands out for its advanced experimentation in the distillation sector, not only in France but globally. We're talking about Rozelieures, in Lorraine, one of the few distilleries in the world that manages all production phases: a closed supply chain thanks to owned fields, the company's malt house, and even the availability of precious woods from which the barrels come in which the distillate is aged. Behind this project is the Grallet-Dupic family, who founded the company in 1860 and have been managing it generation after generation. Rozelieures, with a century-old experience in fruit distillation and, in particular, the traditional and highly territorial mirabelle, has emerged in recent years as a protagonist in the world of "made in France" whisky. Its flagship is Parcellaire, an experiment strongly tied to the land: each year, the company presents two different labels from barley (and malt) grown in different fields of the estate (essentially true cru). For example, one of these whiskies is distilled from barley grown in a plot near the course of a very muddy river and is presented alongside another label derived from different barley grown on a clayey hill. The two whiskies, produced separately a few hours apart and aged in the same wood, offer a horizontal tasting of two twin but non-homogeneous products, where the only difference is the terroir. In practice, France is writing the history of whisky, but perhaps the world has not yet noticed.

The interior of the Chopin distillery, which produced the world's first "premium" vodka. Opening photo by Maxim Fesenko / iStock.

It's quick to say potatoes

Founded by Tad Dorda in 1993 – right after the end of the USSR – in Poland, Chopin Vodka was perhaps the world's first premium vodka. At the core of its production philosophy is the tuber that has been a major player on Polish tables for centuries, namely the potato. For distillation, Chopin exclusively uses high-quality Polish potatoes from farms within 18 miles. This choice preserves the freshness and purity of the tubers, which are then passed four times through a 1896 antique column still. To explain the meticulous work that the company does around the raw material, it is interesting to analyze a particular label, the Chopin Family Reserve: it is made only with early potatoes, the small ones at the beginning of the harvest, and rests for two years in barrels before being bottled. In addition to quality, Chopin is also committed to social sustainability: it buys its potatoes only from family-owned farms that cultivate without the use of chemicals. Here, experimental work and research take center stage. In addition to products that comply with vodka regulations and can officially be marketed with this name, Chopin's long-standing master distiller, Waldemar Durakiewic, actively collaborates with the National Potato Institute to develop single-variety distillates.

Mexico, Mezcal Revolution

In recent years, agave spirits have experienced a renaissance, overcoming the "adolescent phase" influenced by questionable consumption habits imported from the USA. This rebirth is evident in the renewed interest in their potential in mixing and their aromatic complexity in tasting. In this regard, the Mezcal called Single Palenque, created by involving seven local producers in the first single-origin Mezcal label, is extremely interesting. This project requires farmers to commit to producing only with agave grown on their own land and following strict rules: from manual harvesting to traditional oven cooking and spontaneous fermentation. The result is a Mezcal limited to 1,200 bottles per producer: a project that aims to restore meaning and soul to this ancestral production tradition. The project not only pays producers but also allows them to see their name and face on the label: an invaluable victory for those who have been anonymous and exploited protagonists for years. Just like with wine, they are starting to put their face on it.

Luca Gargano, a Rum selector, is associated with the agricultural rum project in Haiti.

Rum, last stop: the island of Haiti

In the Caribbean, the distillation of sugarcane by-products has a history of over 3 centuries. Over time, however, this tradition has increasingly moved away from the agricultural dimension to embark on intensive industrialization: today, there are fewer than 50 distilleries in operation. Imagine the surprise of Luca Gargano, one of the world's leading experts and selectors, when he first arrived in impoverished Haiti, forgotten by multinationals, where there are still about 500 artisanal distilleries anchored to villages and countryside producing agricultural rum from pure sugarcane juice. Contrary to the industrial trend, Haitian Clairins are obtained from a single distillation that preserves the aromatic notes of different local cane varieties. Gargano has become their ambassador worldwide and, to preserve their genuineness, has imposed precise rules on farmers who want to work with him: from organic cultivation to manual harvesting, to transportation by cart to preserve quality. Gargano has selected five varieties, defining strict production criteria: fermentation with natural yeasts for at least 120 hours, distillation in stills with a maximum of 5 copper plates in direct contact with fire, bottling at the exit degree of the still, and it must be made mandatory in Haiti. This specification aims to preserve the authenticity of Clairin and paves the way for anyone wishing to extend this type of production.

Where to eat in Ariccia. The best addresses selected by Gambero Rosso

Where to eat in Ariccia. The best addresses selected by Gambero Rosso The 'electric tomino', the unknown specialty of Piedmontese taverns. What it is and where to eat it in Turin

The 'electric tomino', the unknown specialty of Piedmontese taverns. What it is and where to eat it in Turin To be shared and enjoyed together. The return of Italian appetizers that have conquered Michelin-starred chefs

To be shared and enjoyed together. The return of Italian appetizers that have conquered Michelin-starred chefs The 8 best Vitovska Wines from Friuli Venezia Giulia selected by Gambero Rosso

The 8 best Vitovska Wines from Friuli Venezia Giulia selected by Gambero Rosso History of the hidden specialty coffee shop in an agricultural market in Rieti

History of the hidden specialty coffee shop in an agricultural market in Rieti