Viticultural Tuscany is in trouble and, like Piedmont – not without some strong stances – is questioning what strategies to adopt in view of the 2025 harvest campaign. The election of Andrea Rossi (Vino Nobile di Montepulciano) as head of AVITO (the association uniting the supervisory bodies of Tuscan PDOs and PGIs), replacing Francesco Mazzei, will now initiate a delicate dialogue with the agriculture department led by Stefania Saccardi. A meeting with the wine consortia is scheduled for 15 July (the third meeting of the Wine Roundtable in 2025), and will take place against a backdrop of a very difficult first half of 2025 for Tuscan wine.

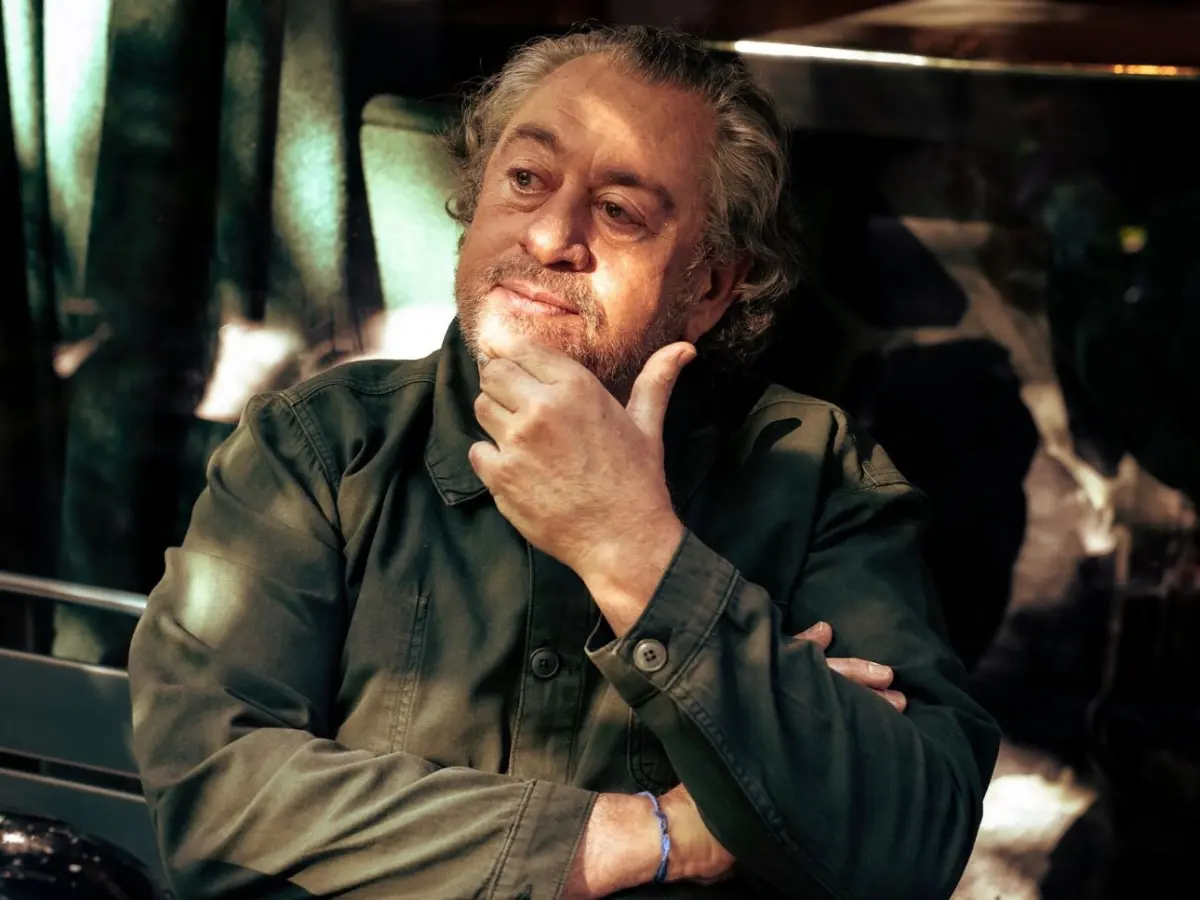

There is no doubt that the decisions of the Chianti consortium – the region’s most significant PDO, representing over 30% of volumes – will be crucial for the regional budget in the ongoing dialogue between institutions and businesses regarding intervention measures. But according to Giovanni Busi, president of the Chianti Wine Consortium, recently re-elected for the 2025–2028 term, decisive action is needed to restore market balance and avoid what he defines as an “unsustainable” situation. His reasoning: it is not viable for the Region of Tuscany to grant 600 hectares of new vineyard planting each year while designations like Chianti are forced to continually reduce yields. In 2025, as previously reported by Gambero Rosso in early June, the reduction – already approved by the Chianti DOCG assembly – will be 20 percent, but more must be done. “Everything must stop for five years,” is the consortium’s demand, calling for a multi-year freeze on new authorisations. This would allow the market time to recover in what is hoped to become a more favourable global context.

In this interview with the weekly Tre Bicchieri, President Busi addresses the measures for limiting production, drawing some clear lines: “Grubbing-up is like a defeat, and distillation and green harvesting are only temporary solutions. The real issue lies in wine promotion and its funding.” But there is more: during this turbulent year, the Tuscan DOCG is technically and oenologically considering the opportunity to create a more modern Chianti – fresher, more appealing to younger generations. In short (as with Prosecco, Pinot Grigio, Garda, Sicilian Nero d’Avola and Orvieto), a low-alcohol Chianti.

President, how would you describe the current state of Italian wine in one word?

Absurd.

Meaning?

Total confusion. Trump appears on television making statements that he then fails to honour and are hard to interpret. And if the nonsense – pardon the expression – comes from the American president, then it’s worrying. Then there's Russia, with Putin still set on Ukraine. And Israel continues bombing.

Yet, in a time of great change like this, Chianti has chosen you once again...

In November 2024, I had begun talks to find someone to replace me. But as I spoke with various parties – from industry, cooperatives and agricultural organisations – I was told repeatedly that it was necessary for me to stay, due to the need for stability. This has already happened twice before. And to think I became president when Chianti was priced at 98 cents in the mass retail channel. I always say I’ve yet to enjoy the good times. But here I am, and we press on.

Let’s try to understand the current state of Chianti. What’s the situation with unsold stock?

This is the most difficult and worrying aspect. As usual, many businesses have signed contracts and received orders from bottlers. However, the bottlers are not collecting the wine because they’re waiting to empty their own warehouses. This didn’t happen in previous years. And it’s concerning because it means even the bottlers are feeling the strain.

What about bottling activity?

Bottling is in line with previous years but 8% below historical standards. So, we are maintaining Chianti sales volumes (June 2025 closed with -3% since January), but it must be said that both 2024 and 2023 were below 2022.

What’s the situation in terms of production prices?

We’re at around €100–€120 per quintal. That’s very low. Ideally, Chianti should sell at around €140 per quintal to be sustainable. This situation is putting significant pressure on businesses, because even at these low prices, the product isn’t moving from the cellars.

I imagine you’re not the only ones in Tuscany facing this...

We’re not alone. Other denominations are also struggling to move their wines. It’s something we need to talk about. Let’s say it’s dark times for everyone.

Can we say the Chianti DOCG is in crisis?

You can say that – but only from a sales point of view. I wouldn’t use the term “crisis” for the DOCG as a whole. I believe the sales crisis is tied to economic issues: people simply aren’t buying. Let me explain with an example from the pandemic: Chianti sales boomed because people were at home, spending less. At the supermarket, among all the wines, Italians chose ours. What did that mean? That the DOCG’s reputation is good. So, I can’t say Chianti is facing a reputation crisis, but rather an economic one, because consumers are buying less.

You’re calling for a multi-year freeze on planting authorisations. Councillor Saccardi is open to the idea, though the final decision lies with the Conference of Regions...

Our assembly voted for a 20% reduction in yield per hectare for Chianti DOCG grapes. But since we are entrepreneurs and must generate income and support our businesses, it’s not right that Chianti reduces production by 20% while the Region of Tuscany allows vineyard planting equivalent to 1% of the regional surface – that’s 600 hectares. Plant them the first year while I reduce yields, fine. But not beyond that. This sacrifice should be shared. Chianti, which accounts for over 30% of regional production, has long called for a surface freeze. We can’t be the only ones to make sacrifices.

Where are these new hectares going?

Mainly into Toscana IGT vineyards – which clog the market. A five-year pause would be appropriate.

Would a drastic measure like voluntary grubbing-up be viable in your DOCG area?

What other option is there?

Promotion. I propose that the Region of Tuscany increase overseas wine marketing budgets by 20%. When Gianni Salvadori was agriculture councillor, Tuscany added 20% to the 50% grant provided by the OCM regulations – so we ended up promoting wine with 70% public funding. To be clear: we’re not asking for more to reduce our responsibility as businesses. We’re asking for more to increase our promotional efforts. We’ll discuss this with the unions at the end of July.

Which markets should be explored?

Without neglecting the traditional ones like the USA, Germany and Northern Europe, there are two regions we must focus on. The first is South America – Mercosur countries. Many Europeans and Italians have emigrated there, and they already know tannins, so no education needed. If a bottle hits those markets at the right price, consumption follows immediately. Many Chianti producers sell in Brazil, but in small quantities due to high tariffs. If those drop, minimal effort will be needed. At the end of 2025, the Consortium will be in São Paulo – hopefully with the Mercosur agreement ratified.

What’s the second target market?

Southeast Asia. Chianti first went to China in 2010, with 50 producers. They looked at us like Martians. Some even asked why Italians made wine. Over the years we expanded and gained importers for each winery. Sadly, COVID halted everything. Now, we’re starting again. I’m also looking at other countries – Thailand (which has reduced wine duties), Japan, South Korea, Vietnam (a growing market). For the first time, we’ve been to Taiwan. Many importers we meet don’t carry Italian wine – only French, Spanish, etc. There’s room for us.

Grubbing-up is like a defeat. Let’s focus on selling the product rather than temporary fixes. Grubbing-up, even in a global crisis, is drastic. Many businesses want to do it, but first let’s see if someone wants that land and can use it to keep producing Chianti – solving the problem for struggling growers.

How are your cooperatives doing?

Let the numbers speak. In 2010, when I became president, we had about 3,500 companies over 14–15,000 hectares, with a total potential of 16–17,000 hectares. In 2025, we have 2,500 companies, cultivating 14,000 hectares with a 17,000-hectare potential.

So, there’s a consolidation trend.

Yes. Many have left, others have expanded. We’ve seen consolidation at the cooperative level, too. What does this tell us? If companies are increasing surface area, there’s confidence in the DOCG. Also, bigger vineyards mean lower production costs. That’s why I say: keep grubbing-up in the drawer. Let’s wait.

What do you think of the proposal by Fratelli d’Italia’s regional councillors regarding distillation and green harvesting?

Distillation is also temporary. If it’s paid €20 per hectolitre – like in Puglia during COVID – it doesn’t help. You’ve spent funds that could have been better used elsewhere, with no real benefit to farmers.

What are you doing in new markets?

In January 2026, we’ll go to Nigeria for the first time to see what the country can offer – with 250 million people, it’s one of the biggest Champagne consumers.

Final question on new consumers and opportunities for wineries. Should Chianti DOCs consider dealcoholisation?

I’m not against dealcoholisation. But right now, dealcoholised products don’t reflect the typical organoleptic qualities of a grape or region. If I make a dealcoholised Chianti, I want to taste Chianti in the glass. So, regardless of your stance, more research is needed on dealcoholised wines.

Perhaps low-alcohol offers opportunities?

It’s worth investigating. I’m in favour, and we’re already moving in that direction.

Are there pilot tests underway?

We’re experimenting with wines around 10% alcohol. Until now, we’ve said Sangiovese needs to reach phenolic ripeness. Today, if we want a 10% wine, we need to study. As a consortium, we’re considering involving the best oenologists. We’re talking about it. In general, if territorial identity is respected, a lower-alcohol Chianti that meets market demand and consumer tastes is welcome.

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day 'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca

'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market

Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers

Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers 'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'

'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'