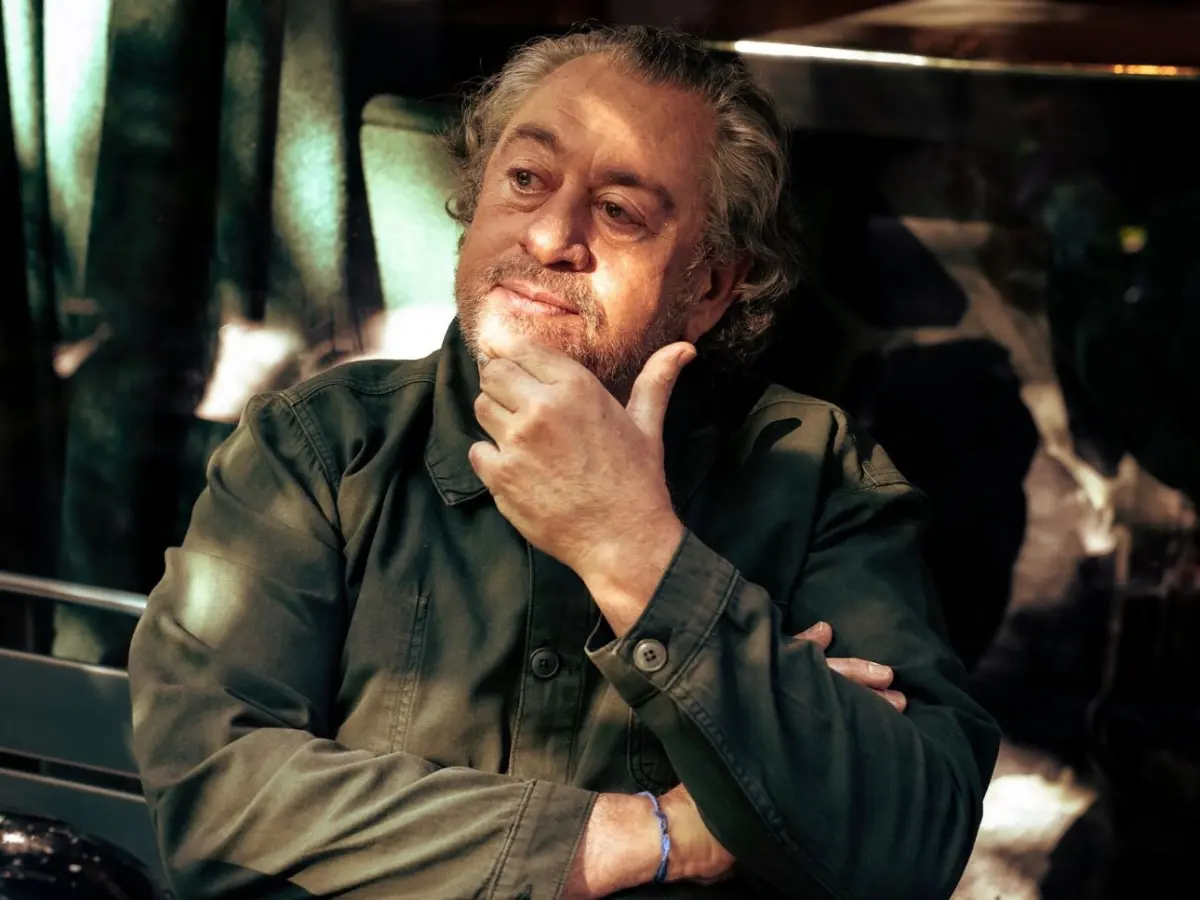

Mauro Uliassi is 67 years old, has three Michelin stars and three Gambero Rosso forks at his eponymous restaurant in Senigallia. Ask his colleagues who their favourite Italian chef is, and six out of ten will name him. We spoke with him in his restaurant, him standing like a little soldier on duty.

Mauro and Catia Uliassi at their seaside restaurant in Senigallia

Interview with Mauro Uliassi: Avant-garde and history

We start with a word dear to Chef Uliassi: avant-garde. What is it?

"Avant-garde means always looking beyond your own truth, having the ability to do so. There are moments more suited to it, others in which avant-garde may not seem such, but it’s still a path someone takes—and perhaps only later it’s understood. Take the avant-garde that happened in Spain during Ferran Adrià’s time."

Let’s talk about it, chef…

"It was linked to a socio-cultural and historical moment in Spain. Spain had just come out of Francoism, it was dirty and poor but had created an incredible energy. In 1983—I remember—I was in Barcelona, and everyone seemed out of their minds, all high on cocaine, super energised. And within four or five years, this euphoria turned into business. In architecture, there were Bohigas and Calatrava; in cinema, Almodóvar; there were musicians—but before that, who knew a single Spanish musician? And in cuisine, there was Adrià—who, had he grown up under Franco, would’ve made paella."

A version of Chef Uliassi's Pasta alla Hilde

From Grandma’s Kitchen to the Lab: Emotions, not Recipes

Right now in Italy, people talk more about “nonna’s cooking” than avant-garde cuisine… So we ask the chef...

What does Grandma’s cooking mean to Uliassi?

"I deeply believe in the familial heritage of cooking—not so much as a transmission of recipes, but as the transmission of an idea of pleasure, care, and attention. As a child, Sunday lunches were a ritual, and that’s where I learned that food can create anticipation, desire, emotion. Watching my mother—and my grandmother when she was around—was like witnessing a simple but powerful act of love. I think that kind of emotion, that intimacy born around a table, is still the foundation of my cooking today. I didn’t take any specific recipe from them, but I absorbed an attitude, a sense of taste rooted right there."

What else inspires you?

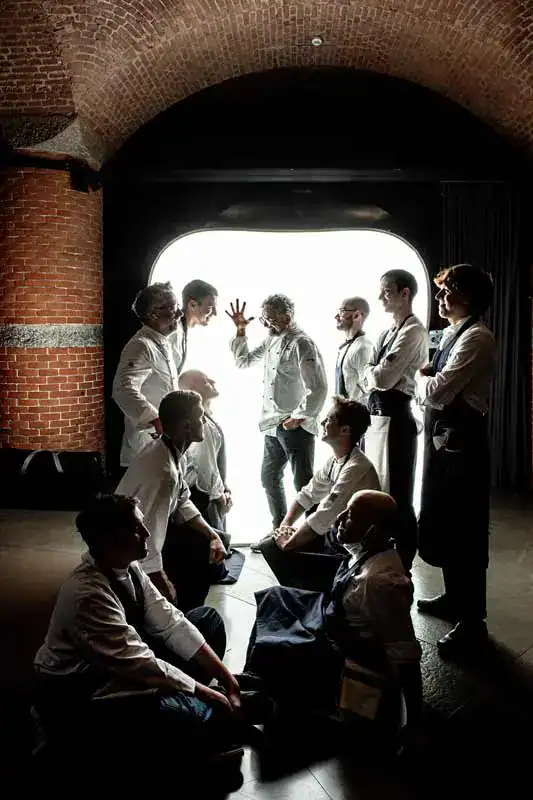

"Every year we close in December, then travel for a month, and from the 10th of February to the end of March, eight of us sit around a table and share our ideas for the new menu. We’re convinced that the creative power of one person doesn’t compare to the creative power of eight—the ideas multiply, we influence each other, creating a mad universe. Think of roast chicken."

Roast chicken?

"Yes. If you ask eight people, each from different backgrounds and who have travelled the world, to think of roast chicken turning on a spit, the chicken will go a thousand ways—and you never know where it will end up. Of course, this creative energy must be codified. We have a precise protocol with two key elements."

Which are?

"Authenticity and simplicity. Simplicity because everything we create must be easily executable by everyone, economically accessible, and with readily available ingredients."

And authenticity?

"You must tell a story that is true—not hearsay, not imitation. You can serve sea bass in Valle d’Aosta, especially if you’re from Senigallia, but it won’t have that authentic depth. There’s no fish there, people don’t know it, and you don’t have the elements around you to cook sea bass purely, clearly. There's nothing to be done: you have to cook sea bass when the scent of the sea is under your nose."

So is yours a zero-kilometre cuisine?

"Not at all. Take Senigallia: it used to be full of marshes, and coastal Marche cuisine consisted of snails, frogs, eel, game, and vegetables. There was fish too, but it was a side thing—farmers who sometimes fished. Today, none of that remains, but if I want to tell the story of my people, I have to get the snails from Cherasco, frogs from France or Hungary, eels from Comacchio, and game from a farm. Zero-kilometre is carnival romanticism. If we accept that principle, we shouldn’t eat bananas or pineapples, and we should only drink Verdicchio."

So is the concept of territory overrated?

"When approaching your work, you have to ask yourself what’s better: pretend to cook with what the territory offers now—when it offers nothing—or tell the story of what no longer exists, but which you have the culture and memory to recall?"

Back to the Lab, the menu born each year from this brainstorming…

"When we sit down and begin our research work, we focus especially on the five senses—because it’s through them that memory is formed. Without your senses, you wouldn’t have memory. And of all, the most important is smell: you might not eat a basil leaf for three years, but if you smell it, you’re instantly back where you were three years ago. The senses are the hic et nunc—you can’t move from there."

What’s the principle behind each new Lab?

"The principle of desire. We no longer eat for the peasant hunger of our grandparents but for pure pleasure. And pleasure operates on other levels—desire. I must make you want things or spark your curiosity. If after four dishes I keep offering the same textures, same aromas, you’ll get bored. Instead, I must ensure that when you finish one dish, you’re slightly sad and eager to see what comes next."

On the menu there’s the Lab, but also the Classico.

"Actually, the Classico dishes are all former Lab creations—every year, the most universally loved dish enters the Classico. The Cuttlefish is from 2022, the Sea Urchin from 2022, the Lamb from 2023, Smoked Spaghetti from 2008, and the Amberjack from 1999. And every year, a new dish replaces another."

You received your first Michelin star in 1995 but only reached real fame in recent years. Why do you think that is?

"I’m slow."

Really?

"Let’s put it this way: I’m extremely consistent. With my sister Catia, we always took small steps and tried to make sense of both success and failure. Success is the past participle of the verb ‘to succeed’—once it’s happened, it’s over. Celebrate for 48 hours, get drunk, then look ahead. We were never in a rush. When we opened the restaurant in 1990, the only thing that mattered was having it full at lunch and dinner—nothing else mattered."

Was it full?

"After eight months we had queues outside—we were buzzing. In the evening, we’d open the till and couldn’t count the money in it. We could’ve bought a Porsche, a Rolex each—but thanks to our parents’ peasant teachings, we reinvested everything into the business."

What does working well mean to you?

"The ‘good’ I envisioned at the beginning isn’t the same as I see it now, but the desire remains the same. For us, working well means cooking well for our clients, having a team in harmony with us, sharing success with others: this creates a virtuous cycle where your dreams slowly become reality. Otherwise, you might as well grab a revolver and go rob a bank."

What was it like being recognised by the critics?

"In the early years, we had rats the size of cats because the port was nearby. When the wind blew, we had to keep the windows shut because rain and sand would come in. I still remember a German client and his comb-over... (laughs). We weren’t thinking about Michelin stars—we only saw nearby horizons. Each time we reached one, we lifted our heads and saw another—and slowly, magically, blessings rained from above."

Did you never dream of entering the fine dining circle?

"The first three-star restaurants I visited were Joël Robuchon’s Jamin in Paris and Alain Ducasse’s Louis XV in Monte-Carlo. And I thought: if this is three stars, we’ll never see them. How could we? Billion-dollar investments, grandeur, gold, stucco, tapestries—that’s what it looked like. Yet, at the same time, I told myself that what we were cooking wasn’t so bad."

And yet, here you are…

"Look, I’m happy. But for us, client satisfaction always came first—only later did we understand the critics’ importance."

What do you think of today’s Italian food criticism?

"One day Stefano Bonilli asked Ferran Adrià: what do you think of critics? And he said: critics are fantastic when they speak well of you and badly of others—they’re bastards when they do the opposite. But I also believe what art critic Francesco Bonami said in an interview: critics must do their job—and those criticised shouldn’t whine."

Crystal clear. Has there ever been a dish you believed in that didn’t land as expected?

"No, because when something doesn’t work, I toss it without issue. Also, something can always come back later—no work is ever wasted. I remember a crazy dish we made in 2010: crispy onion with oyster ink and rosemary. Back then it puzzled people, but we revived it in other contexts with great results."

Should a chef insist or listen to the public?

"Chefs are naturally presumptuous—they presume, otherwise they wouldn’t open a restaurant. If I didn’t believe my palate could satisfy 95% of people, I’d have been mad or delusional. A little arrogance, in a positive sense, is necessary."

You and your sister Catia…

"Catia and I are the restaurant—with the five or six people who’ve been with us from the start. One of them even married her—and they all have power over everything."

You have two children…

"Yes. Rosa is a professional journalist and philosopher—she helps with communications and always tells me to watch my mouth. Filippo works with me—he’s maître with his partner Elisa."

Did you push them to work with you?

"No. This is a job you do with great enthusiasm. When I opened this place, I used to sleep here—it was the most ‘mine’ thing I had. You have to feel these things."

Do you see yourself as a mentor?

"You can only be called a mentor by others. It was never my ambition, but if others recognise it, I’m pleased… though it surprises me."

Some of your peers boast about it. Do you have friends among fellow chefs?

"Chefs are all the same—it’s always a bit of a competition. First local, then national or international. Everyone elbows their way forward, knife between their teeth, trying to come first."

So, no friends then?

"Come on! I have wonderful relationships with many colleagues. I’ve had the luck to be part of two great generations: one, with Vissani, Pierangelini, Iaccarino, Pinchiorri, Marcattilii, where I was the youngest. And the other, with Bottura, Scabin, Alajmo, Crippa, Romito, Sultano—where I’m the oldest."

Do you feel old?

"Getting three stars later in life makes me feel like Dino Zoff winning the World Cup at 41: it makes me feel in the game. But all the ambitions I had when I was younger—I don’t have them anymore. There's a big difference between getting three stars at 60 and at 45. At 45, you’re more aggressive, full of energy—success makes you hungry, everyone’s on you, offering things—and because they offer a lot of money too, it’s hard to say no. At 60… I exercise, do yoga, all that—but when I look ahead, the road feels shorter. I no longer think life is infinite."

Are you obsessed with staying fit?

"Not really—but in this job, it’s crucial to stay sharp and strong. Otherwise, as we say in Senigallia, you won’t even eat the capon."

You also practise Transcendental Meditation…

"I started in 2014 after seeing David Lynch on Fazio’s show—he talked only about that, and I found it very compelling."

I tried it once too—didn’t work.

"But with meditation, you have to persist. If you don’t give up on her, she won’t give up on you."

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day

The Paris restaurant where a different tasting menu is served every day 'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca

'Balance between evolution and continuity': the identity of Conti Zecca Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market

Why the Italian wine industry should 'stick to it' in the US market Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers

Langhe Nebbiolo DOC in bag-in-box: the rule change dividing producers 'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'

'Wine knowledge in Nigeria is evolving'